By Travis Freeland and David V. Burley

Burial mounds are widely scattered across the Tongatapu landscape. When you land at Fua’amotu airport, they line the runway. When you drive into Nuku’alofa, they can be seen to either side of the road. And if you take a bicycle down any field track in the countryside, they are continuously encountered and occasionally ridden over.

All but a few are without name, and the individuals buried within are long lost to history. Yet these mounds represent a story that literally is inscribed on the Tongatapu landscape. It is a historical geography that we can now record in its entirety through the technological advances of airborne LiDAR.

Tongatapu LiDAR

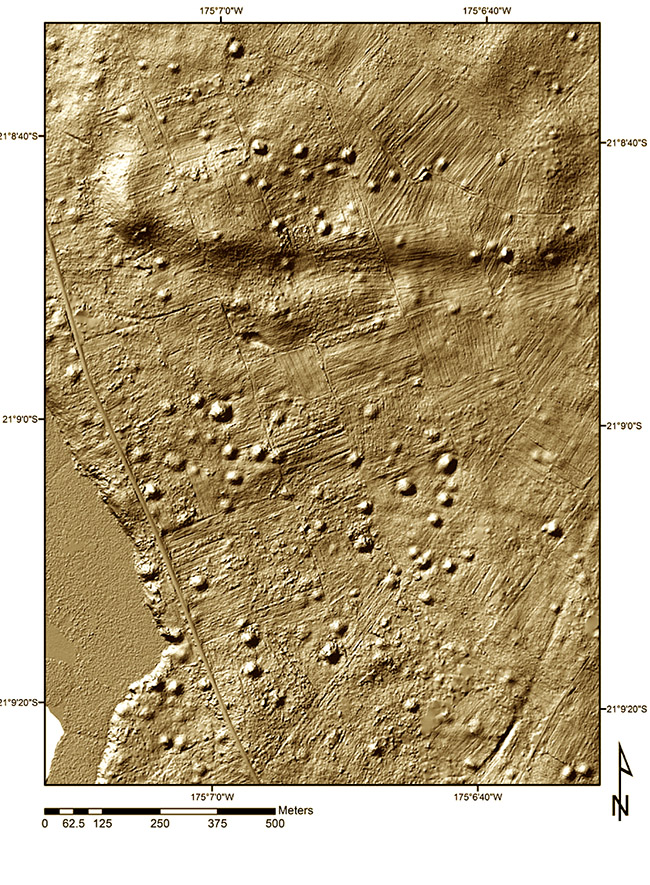

The collection of Tongatapu LiDAR data was funded by the Australian government in 2011 and given to Tonga as part of a tsunami risk assessment project. Its intended use was not for archaeology, but it offers a powerful tool to study the archaeological past. The data provide a laser scan of the island’s land surface taken from an aircraft. Laser pulses of light were beamed to the ground with their reflection providing accurate measures of distance.

Landscape topography could then be mapped in 3-dimensional imagery, with vegetation cover and modern structures removed through computer manipulation. This reveals in detail an astonishing array of mounds, ditches, and other earthworks constructed in Tongan antiquity.

Landscape of mounds

Our immediate observation of the LiDAR images for Tongatapu was to note a stippled appearance, one comparable to the surface cover of a basketball. There were hundreds or even thousands of identifiable bumps spread across the island from east to west. These were burial mounds, some large, up to 60 metres in diameter and several metres high, others much smaller with heights of a half metre or less.

We did field checks in 2014 and 2015, visiting a sample of the sites to record more detail, or ensure they were what we thought they were. A computer application based on shape recognition was developed to identify, record and count the mounds. The accumulated total was astounding, including upwards of 10,000 of these sites. Given the land area of Tongatapu (257 km2), there are close to 40 mounds for every square kilometre.

Not all mounds were used for burial; some were constructed for pigeon hunting (sia heu lupe), some as sitting platforms (esi) and a few potentially were constructed as a house platform. The vast majority though were built for interment of the dead.

Increasing Use of Mounds from the 12th to 18th Centuries AD

There has been limited research conducted on Tonga’s ancient burial sites, save for the massive complex of langi at the former capital of Lapaha.

Excavations at two mounds in ‘Atele in the 1960s, and occasional disturbance of mounds by modern development, illustrate that the number of burials in each is large, perhaps ranging up to a hundred or more.

The beginnings of mound building occurred sometime in the first millennium AD with widespread use by the 12th or 13th century AD. The early mounds are not elaborate. They have no burial vaults, use of coral sand, or kilikili. Each of these features came later, as chiefly tombs became symbols of rank and authority.

Rectangular, squared and tiered burial mounds faced with stone for the Tongan élite reflect further upon the growing political landscape of an emerging Tongan state. These sites, too, are observed on the LiDAR images.

Different settlement landscape

The plot of burial mound locations on a map of Tongatapu tells us much about the pattern of settlement from 1200 AD into the 19th century. These features occur everywhere, from coastal margins across interior field systems. They represent a time when villages, if they existed at all, were rare.

The early capitals of Tonga at Toloa, Heketa and Lapaha are the exceptions. Chiefs established themselves on their estates and scattered their people across the land. The mounds are the resting places for these kainga. This pattern of settlement ensured a loyal following while preventing encroachment from chiefly rivals.

That arrangement continued to be present on Tongatapu in 1777, when Captain Cook was given to write - Here are no towns or villages; most of the houses are built in the plantations, with no other order than what conveniency requires. It was the time of fanongonongotokoto, where news could be shouted from one household to another, and travel from one end of the island to the other. The map of Tongatapu burial mounds stands as visible testimony to the structure of this settlement.

People missing from history.

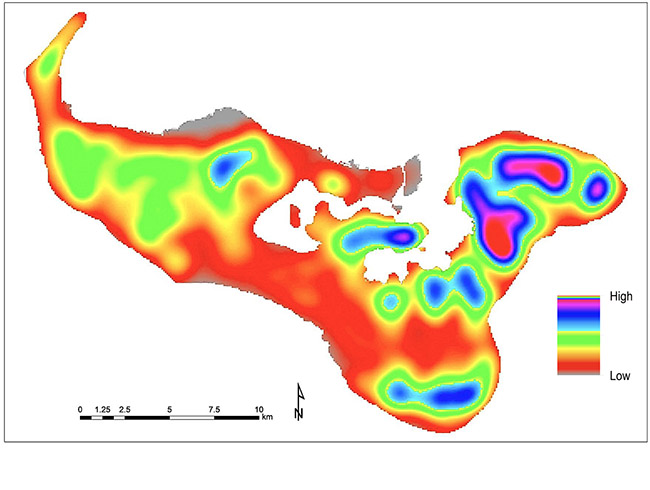

Where there are significant numbers of dead, we assume there was an equivalent number of living. The Tongatapu burial mounds provide a relative measure for gauging the distribution of people across the island over the past 900 years.

The map of burial mound locations was turned into a density distribution plot with colour codes used for mound concentrations or areas where mound occurrences are lower. The densest swath of mounds, not surprisingly, extends from Lapaha inland to the south, illustrating the extent of the Tu’i Tonga’s people.

What is surprising is an almost equal sized density cluster across the eastern end of Tongatapu. The relatively thin population here today begs the question of what happened in history?

The answer may be far more involved, but events of the 19th century civil war provide at least a partial explanation. This was the 1801 battle of Poha, as later written about by the Missionary John Thomas. The western chief Vaha’i waged war across this area in revenge for the murder of Tu’i Kanokupolu, Tuku’aho. The dead became so numerous that they were laid across each other in large piles and eventually burned. The consequence was described as “Ko e Tunu ’o Vaha’i” (the broil of Vaha’i). Survivors fled quickly.

Pyramid of Nukunukumotu

Scrutiny of the LiDAR images for Tongatapu has identified one mound as significantly standing out. This is the Pyramid of Nukunukmotu, as we have begun to call it. It is located above the eastern shore at the entrance to Fanga ‘Uta Lagoon.

The pyramid is formed as a squared mound with the base 60 m on a side. It has sloped sides rising to a height in excess of 6 metres with a flat platform top. It is not a burial mound, at least as could be determined in the field. Nor does it appear to have been constructed in the modern era. The pyramid has an estimated volume of 12,500 cubic metres of fill, making it one of the most substantial structures in all of Tonga.

We can only guess as to what it was used for. Its prominent position at the mouth of the lagoon suggests an observatory to identify in-coming canoes. Perhaps it held a beacon, where the same canoes might identify the channel entrance to Lapaha. But whatever the function it might have had, it must have been important. The scale and labour in its construction speak clearly to that.

Travis Freeland is a consulting archaeologist in Terrace, BC, Canada. He completed his PhD in 2018 at Simon Fraser University with a dissertation study on the mounds of Tongatapu.

Dr. David V. Burley is a Professor of Archaeology at Simon Fraser University in Burnaby, BC, Canada. He has carried out archaeological studies in Tonga since 1989.

More articles in this series:

- Ha'apai rock art suggests Hawaiian link about 1400-1600AD

- Giant Tongan fruit-gulping pigeon eaten into extinction

- The last Fale 'Otua in Ha'apai

- 'Ata and its archaeology

- The Lapita origins of Tongan ngatu and design

- Scarcity in Paradise

- Early settlement of Ha‘apai brilliantly laid title to islands

- Taupita –Tonga’s earliest known game

- The first Tongans