The first human settlements of Vava‘u between 850-810 BC faced scarce fish supplies and limited sustainability of reef foraging efforts. The story of the Lapita people is traced by careful archaeological excavations of their settlements at Ofu, Pangaimotu, Otea and Falevai, marked by the pottery fragments they left behind.

By David V. Burley

Vava’u is as close to a tropical paradise as one can possibly imagine. Calm sheltered harbours, blue-green lagoons, white sandy beaches, numerous offshore islets, steeply rising slopes covered in lush green foliage, and breath-taking scenery are images immediately coming to mind. Expectations were high in 2003 as I planned an archaeological project to focus on the islands’ first residents. With three seasons of field work in the plan, it was difficult not to smile.

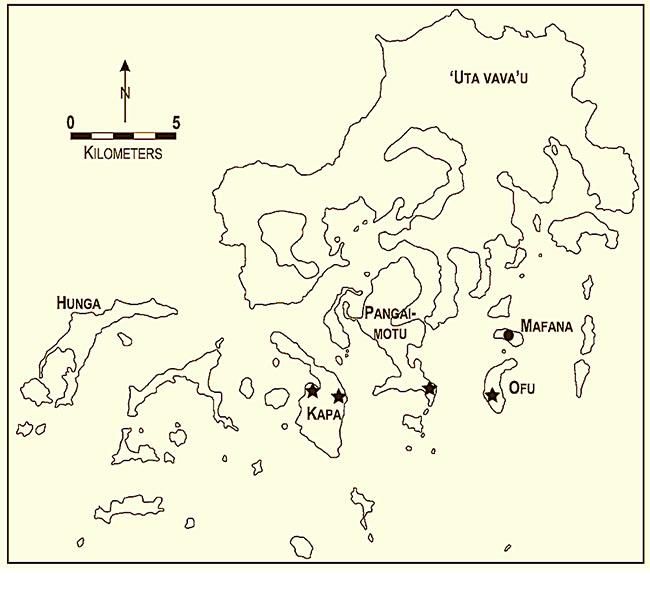

The coral limestone islands of Tonga began to emerge from the ocean two and a half million years ago. ‘Uta Vava’u, the largest island in the Vava’u Group, was the first to appear. Eventually formed as an expanded series of platforms, it now loftily rises to over 200 metres on its northwestern coast. Vava’u Tahi, incorporating the 70 other islands in the group, are strewn southward, with ever diminishing size as they stretch toward Ha’apai.

The Vava’u project began with surveys on ‘Uta Vava’u and 23 other islands where human settlement may have been possible. Finding Lapita sites is always a complex and difficult task, one needing to consider ancient changes in landscape, sea level and numerous other factors. The search in Vava’u was enhanced immensely by regional geology. Island subsidence had been in sequence with falling sea levels since the time of human arrival. The shorelines examined in 2003 were pretty much the same as encountered by the first Lapita canoes.

That first season of work was successful in finding sites with decorated Lapita ceramics. These occurred on Mafana island, in the village of Ofu on Ofu island, on the southeast coast of Pangaimotu island, and in Otea and Falevai villages on Kapa island. Archaeological excavations at Ofu, Pangaimotu, Otea and Falevai over the next two years give detail and insight into initial human presence.

People first arrived in Vava’u between 850 and 810 BC, establishing themselves on the south central islands offshore of ‘Uta Vava’u. The earliest sites at Ofu, Pangaimotu and Otea are all but identical in their age, and they are coincidental with the oldest sites in Ha’apai. This can be explained only by a large-scale and intentional expansion of people from Tongatapu through Ha’apai into Vava’u in the latter decades of the 9th century BC. As written of in earlier stories, it was a brilliant strategy, one laying claim to all of Tonga. We also know that the migration continued beyond Vava’u to Niuatoputapu, this documented in the 1970s discovery and excavation of a Lapita site near Vaipoa village.

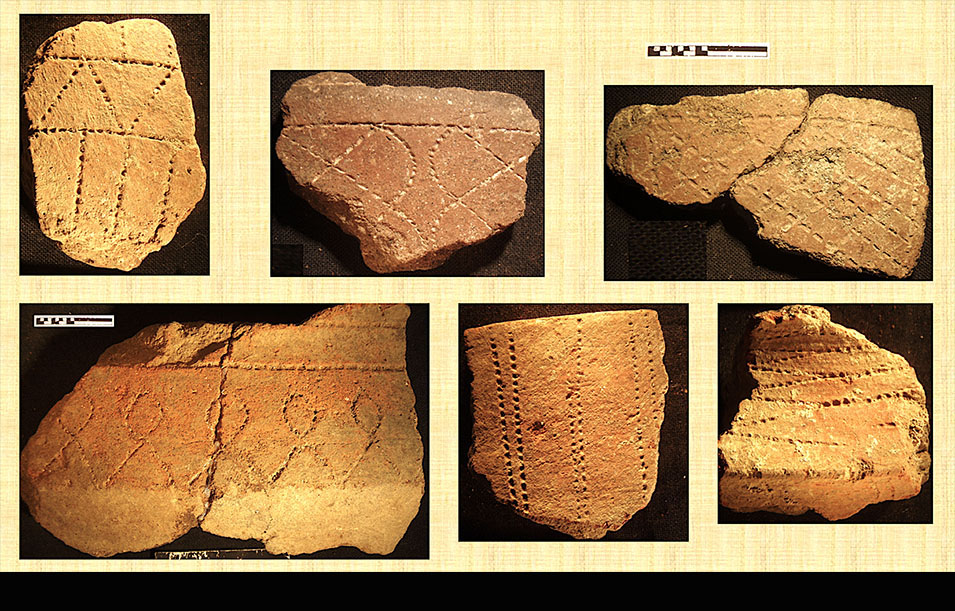

The pottery and other artifacts from Vava’u are typical of Lapita assemblages in Tonga. Ceramic decorations have open and simplified motifs, but where occasional vessels retain complex elements and forms. Other artifacts reflect a concern with personal adornment, including shell beads, rings, bracelets and the like. Fine bird bone needles were probably used to attach brightly coloured feathers to mats and baskets.

The volcanic stone used for ‘umu rock, adzes and other artifacts, was assumed to come from Late, a volcano located 60 km to the southwest. A trip to Late in 2003 to collect samples for comparison turned into an exhilarating adventure as our inflatable dinghy came crashing ashore on an inhospitable coast.

Extinct parrot

Excavations in Vava’u continued to document the diversity of bird populations in Tonga prior to human presence. From excavations on Pangaimotu, an extinct form of rail (veka) was recovered and named Hypotaenidia vavauensis, the name reflecting its presence only in Vava’u. At Ofu, 144 bones were collected from a long-eaten meal of the extinct pigeon Ducula shutleri. This species was 2.5 times larger than the lupe currently found in Tonga. It also is the largest species of Ducula yet documented for Oceania. And from both Ofu and Pangaimotu, bones of the extinct parrot Eclectus infectus were identified. A possibility that this species survived into more recent times may be illustrated in a sketch from the Alejandro Malaspina excursion to Vava’u in 1793.

Vava’u bird life aside, excavations of other types of food remains at these sites have an unexpected story to tell. That story, in its essence, is one of scarcity. Fish remains were shockingly limited! The number of fish bones per 100 litres of excavated deposits at Ofu and Otea, for example, is 98% less than similar measures from Lifuka and Ha’afeva islands in Ha’apai. Shellfish counts and species diversity are similarly impoverished, illustrating limited productivity, or at least limited sustainability, for reef foraging efforts. High sediment influx and limited reef growth in many of the inlets and bays on ‘Uta Vava’u, and reduced biogenic production from low nutrient levels in western Vava’u, amplify the problems even further. The presence of Lapita settlements on the southcentral islands of Vava’u is a clear reflection of this diminished ecosystem.

The inadequacies of the reef for subsistence requirements was consequential for other aspects of settlement. To ensure a community’s food supply, all of the Lapita sites were purposely located next to a wetland or swampy ground. These freshwater enclaves would support taro gardens, even when rainfall patterns were unknown, or where droughts might occur. An American palynologist, Patricia Fall, extracted a core sample from the Avai’o’vuna swamp adjacent to the Lapita site on Pangaimotu island in the late 1990s. Her analysis conclusively identified taro pollen from the period of first human arrival. She also has evidence for Lapita introduction to Vava’u of sugarcane (tō) and cordyline (si).

Polynesian Plainware phase

My archaeological surveys throughout Tonga have not exclusively been related to first settlement. There also has been concern with sites of the following Polynesian Plainware phase. These sites date between 700 and 400 BC and are characterized by undecorated ceramics as the name implies. The Polynesian Plainware phase on Tongatapu and throughout Ha’apai is characterized by major population growth and settlement expansion. This was not the case in Vava’u. Occasional ceramic sherds were found scattered across ‘Uta Vava’u and many other islands, but only twelve small Plainware settlements were identified. Most, again, were located on offshore islands to the south. The Vava’u population remained small long after the Lapita period ended.

Otea kelea

Of the stories to be told from the two seasons of excavation, Otea has the most peculiar. This is not about first settlement at Otea, but an event that occurred sometime between 450 and 550 AD.

As excavations were taken downward through washed in clay, later settlement features and other occupation debris, the crew suddenly encountered a 15 to 20 cm thick layer of compacted shell. It was a rubbish layer, laid down as a single occurrence and without other types of archaeological materials mixed in. The layer consisted almost completely of a single species of sea snail, Strombus luhuanus, or kelea as identified by the Tongan excavators. Kelea are present in other deposits at Otea, but the sheer quantity sets this layer apart. My calculation of the volume extracted from the excavation alone was 2.5 cubic metres, the rough equivalent of 150 wheelbarrow loads. This was more than enough shell to fill the back of a half-ton truck.

What the event represents, where the kelea was acquired, how it was transported to Otea, and how so many were cooked are puzzles unresolved. The Otea kelea stand out as an ecological anomaly on what otherwise seemed a landscape of scarcity.

Dr. David V. Burley is a Professor of Archaeology at Simon Fraser University in Burnaby, BC, Canada. He has carried out archaeological studies in Tonga since 1989.

More articles in this series:

- Ancient DNA provides new understanding of Oceanic settlement

- ‘Ata and its archaeology

- The Lapita origins of Tongan ngatu and design

- Early settlement of Ha‘apai brilliantly laid title to islands

- Taupita –Tonga’s earliest known game

- The first Tongans

- Giant Tongan fruit-gulping pigeon eaten into extinction

- The last Fale 'Otua in Ha'apai