The first article in a series on Tongan archaeology and pre-history, produced for Matangi Tonga by David Burley and other scholars.

By David Burley

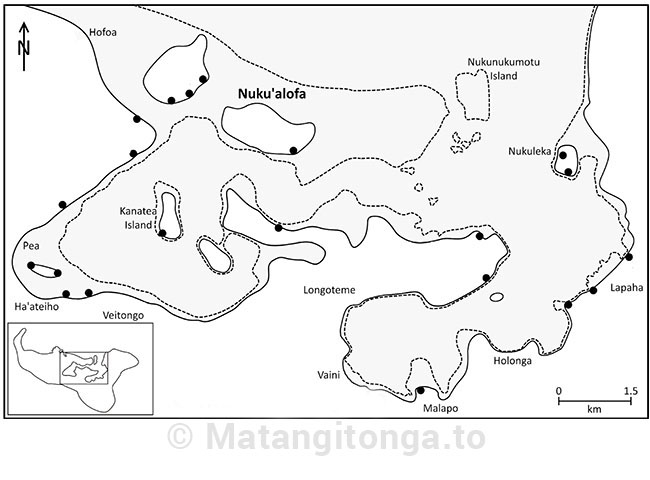

Tongatapu was a far different place 3000 years ago, one few of us can imagine today. The sea was higher, almost 1.4 m higher. Much of the land on which the city of Nuku‘alofa now sits was not land at all. In the place of government buildings, the market, and the downtown core, there was nothing more than reef flat with shoals, sand bars, and some sandy islets, across which the highest tides could ebb and flow. The now-sheltered lagoons were open bays, fringed in part by white sand beaches, not the muck-filled mangrove that eventually emerged as sea levels fell. It was about 900 BC when voyaging canoes first arrived from a homeland to the west. These kalia carried a small group of people and all of the necessities they would need to settle new found islands. They were the first Tongans.

I am an archaeologist, someone who reads the past through the discarded, lost, or otherwise left-behind bits and pieces of daily life, fragments now long-buried in island soils. We are able to track the journey of the first Tongans by a distinctive type of pottery they made, one we refer to as Lapita. These ceramics have highly distinctive decorative designs that were applied to the surface of the pot using a small, comb-like tool. Lapita pottery occurs first in archaeological sites of the Bismarck Archipelago off north coast New Guinea by 1350 BC. Within a century, Lapita potters carried their pots eastward as the exploration and colonization of Oceania began in earnest. Pacific archaeologists have spent the past half century studying the Lapita ceramic trail, and we are able to define regional styles, and the way these pots and their decoration changed over time. Archaeological research in Tonga since the 1960s has identified numerous sites with Lapita pottery on Tongatapu, throughout Ha‘apai, and further north into Vava‘u and Niuatoputapu. Excavations at several of these sites give insight into these people, their lives, and their pioneering efforts to settle the widely dispersed island groups.

The story of the first Tongans begins at Nukuleka, a small, quiet fishing village on a peninsula at the northeast entrance to Fanga ‘Uta Lagoon. For many Tongans, the unremarkable nature of Nukuleka today makes it a puzzling location for interpretations I have made. But the archaeological evidence is clear in identifying it as Tonga’s first village. Excavations here have unearthed tens of thousands of ceramic fragments, other artifacts, and large amounts of shell and small bones from former meals. We also have acquired a large number of radiocarbon and uranium thorium dates to give us an age for the site. One date, from a file-like coral abrader in beach sand at the very bottom of the site, places landfall between 888 and 896 BC. Other of the dates are close in time. There is no other site in Tonga, or elsewhere in Polynesia, with accepted dates of equivalent age.

But it is not just the dates that identify Nukuleka as the founder colony for Tonga. Some Nukuleka ceramics have complex Lapita designs typically found in early sites in Fiji, Vanuatu and the eastern Solomon outlier islands. These motifs occur nowhere else in Tonga or in other sites of west Polynesia. In addition, the ingredients used in some of the earliest Lapita wares from Nukuleka are foreign to Tonga. Geochemical analyses and microscopic studies of minerals tell us that the temper sand and paste ingredients come from somewhere else. We have yet to identify where these ceramics are from, but they were probably carried on the very first canoes, as incredible as that claim might appear.

We can only imagine the scene as the first canoes sailed along the leeward coast of Tongatapu and entered the two large bays that are now Fanga ‘Uta Lagoon. Why they chose Nukuleka as a place to settle remains a mystery, though its access to the open sea would have been critical to a maritime people arriving in boats. At the time, Nukuleka was a small island, where a sand spit was cut off from the mainland by tidal waters. Immediately offshore were sand bars and reef shallows, a veritable supermarket where shellfish, fish and other foods could be easily acquired. The refuse from these activities created “kitchen middens”, thick deposits of organically rich sediments mixed with shell and other rubbish.

The houses at Nukuleka were raised on posts along the foreshore, on sand ridges, or positioned on the reef close to shore. Stilt house construction is another of the traits that people carried from the west, though it was abandoned early on Fanga ‘Uta Lagoon. The Lapita colonists brought with them tubers and seedlings for garden plants and trees, several identified by ancient pollens recovered from the site. The earliest settlers had no pigs or dogs, but chickens were plentiful, and rats had secretly stowed away on the trip. We excavated a planting pit in 2014, where giant swamp taro was grown in exactly the same way as it is today on Micronesian atolls. Thousands of Lapita ceramic fragments were mixed into mulch in the pit to retain moisture from the freshwater lens and release nutrients as the fragments broke down. This pit is another of the Nukuleka firsts, being the earliest evidence for this type of agricultural system yet discovered within the Pacific.

It is impossible to estimate the number of first Tongans who stepped ashore on Tongatapu almost three millennia ago. My guess is a hundred or less. Whether this group was the vanguard for later canoes also is impossible to tell. What can be said with certainty is that the total population was small, and it seems to have grown ever so slowly in the decades to follow. Settlement on Tongatapu, in fact, was almost entirely restricted to the shores of the present-day lagoon until 750 BC. But exploration did continue northward, moving through Ha‘apai, Vava‘u, Niuatoputapu and, quite probably on to Samoa. By no later than 810 BC, small clusters of people with later types of Lapita ceramics were dispersed across many of these islands. These were hamlets containing three to four families at most. Their widespread nature, with one hamlet per island, and the all but instantaneous dispersal throughout Tonga, implies an intentionally planned strategy. It seems a territorial imperative, with different hamlets laying claim to a homeland across far-flung islands.

At one of the sites on the outskirts of Vaipoa village on Niuatoputapu, the early colonists discovered a source of volcanic glass. This was a highly-prized material for stone tool manufacture, one capable of producing a razor-sharp cutting edge. The presence of this glass in early sites of Vava‘u, Ha‘apai and Tongatapu reveals inter-island voyaging, trade, and the all-important maintenance of family and community relations. As a result, there is every indication that the territorial boundaries of Tonga and the integration of its regions occurred early, no more than a century or so after first Tongan footsteps on the beach of Fanga ‘Uta Lagoon.

- Dr. David V. Burley is a Professor of Archaeology at Simon Fraser University in Burnaby, BC, Canada. He has carried out archaeological studies in Tonga since 1989.

More articles in this series:

- <a href="/%3Ca%20href%3D"https://matangitonga.to/2021/01/29/ancient-dna-provides-new-understanding-oceanic-settlement">https://matangitonga.to/2021/0½9/ancient-dna-provides-new-understandin...

- Ha'apai rock art suggests Hawaiian link about 1400-1600AD

- Tongatapu's astonishing burial mounds

- Giant Tongan fruit-gulping pigeon eaten into extinction

- The last Fale 'Otua in Ha'apai

- 'Ata and its archaeology

- The Lapita origins of Tongan ngatu and design

- Scarcity in Paradise

- Early settlement of Ha‘apai brilliantly laid title to islands

- Taupita –Tonga’s earliest known game