By Pesi Fonua

While their political views may differ widely, the one thing that most people agree on is that Tonga as a nation is a special case.

We are special not only because we are very small, with a population of around 100,000, but also because of our experience in self-government. Tonga has had Kings since 910AD, and once had an empire that survived for centuries.

And last century when the rest of the world turned its eyes on the South Seas, the Kingdom of Tonga remained the only country in the Pacific that was not colonised. Following the proclamation of the Tongan Constitution in 1875 Tonga was recognised by the super powers of those days, France, Germany, Great Britain, and America.

Those were achievements of the past, but today the world is a different place and one that places high moral value on the term “democracy”.

While Tonga enjoys a certain status among nations under a constitutional monarchy form of government, any move to replace it with an elected form of government will be a step into the unknown.

Matangi Tonga looks at what different people in the community have to say about their current system of government.

A Sacred Authority

While the western style of democracy with an elected form of government is the trend world wide, and is the model for governments in the South Pacific region, Tonga on the other hand operates under a system of government where the King is sacred and the sovereign of all the chiefs and all the people.

In Tonga [1997], the authority of the King in the Privy Council is the highest executive authority in the Kingdom, and the Prime Minister and the cabinet are responsible for carrying out the resolutions of the Privy Council.

The King appoints all the members of the Privy Council, who are also members of the Cabinet and the Legislative Assembly.

The Tongan Legislative Assembly consists of 11 Cabinet ministers appointed by the king, nine noble’s representatives elected by the 33 noble title holders, and the nine people’s representatives elected by the people.

In the Legislative Assembly, the members of Cabinet meet with the representatives of the nobles and the people. The two main tasks of the Tongan Legislature are the passing of laws and the annual budget. Their working agenda also includes debating such things as the annual reports of Cabinet Ministers, motions, and petitions from elected members. Since 1995 elected members have been allowed also to table bills into the House. If the motions and the petitions are passed by the House, they then proceed to Cabinet for further scrutiny where a final decision is taken. However, bills that are passed by the house go straight to the king for his signature.

Frustration

But the way the House works frustrates the elected members of parliament, particularly the people’s representatives. Most of them feel that their motions, which express the needs of the people, are nothing more than an issue that is raised for the Cabinet to look at, and 90 per cent of the motions become in effect nothing more than, as they say in the House, fakalelea filo pe, hot air.

Elected members of the House, particularly some of the people’s representatives want the people to elect the ministers, and they want the Cabinet to be more accountable to the House.

The Tongan Government was described by the New Zealand Foreign Minister, Hon. Mr Don McKinnion, as a little bit like a combination of the American and the New Zealand Governments. The King appoints his ministers from anyone in the community just as an American President does, while in a similar way to New Zealand the ministers sit in the House. The difference is that in New Zealand ministers must be first elected into the House as members of parliament before they can be appointed to Cabinet.

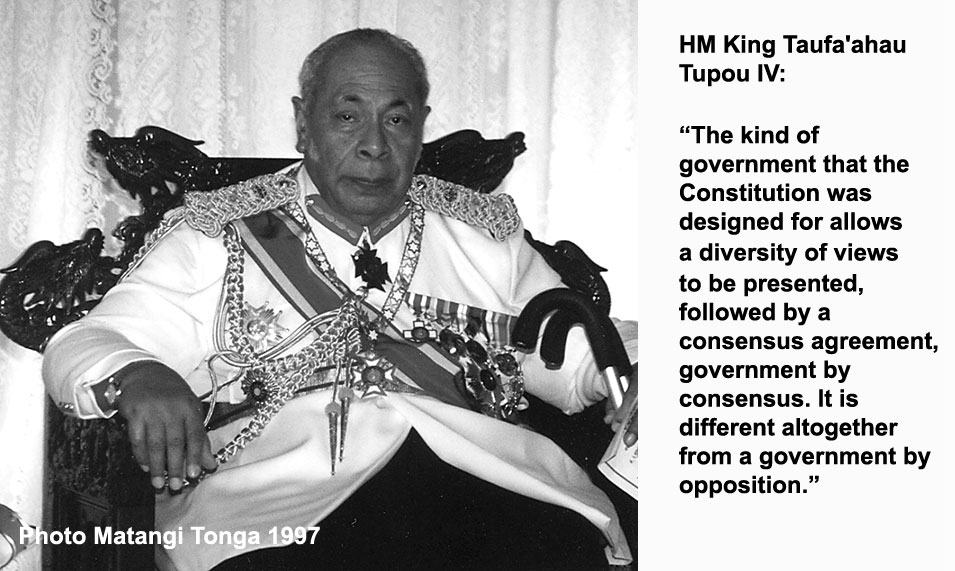

The status of the Tongan parliament in relation to the Cabinet, and the Privy Council is best described by King Taufa’ahau Tupou IV.

The King told the Matangi Tonga in 1990 that: “the history of Tonga tells us that the governing of the country was carried out by the King himself. When parliament was installed it was then carried out by the king in partnership with the nobles, then the people’s representatives were brought in, still to be in partnership with the King and the nobles to work together. Therefore the aim of the government of Tonga is to work together without any opposition. However the aim of the people’s representatives (today) is to form an opposition so that there will always be debates and confrontation which could result in the house being not able to do any work.”

Diversity of views

“The kind of government that the Constitution was designed for was for a diversity of views to be presented, followed by a consensus agreement, government by consensus. It is different altogether from a government by opposition.”

The King went on to say that there is no other Government like the Tongan government, “because no one else has a history like Tonga’s. In the English speaking countries there was a war between the King and the parliament, and parliament won, and parliament rules. But in Tonga the war that took place was by the King and the people against the rule of the chiefs, and the King was the champion of the people, not parliament because there was no parliament. “This was clearly illustrated when the members of parliament walked out of the House, they tried to sabotage the parliamentary system, but the system was not designed to function like that and it continued to function normally (in their absence). It cannot be sabotaged by elected members,” the King said.

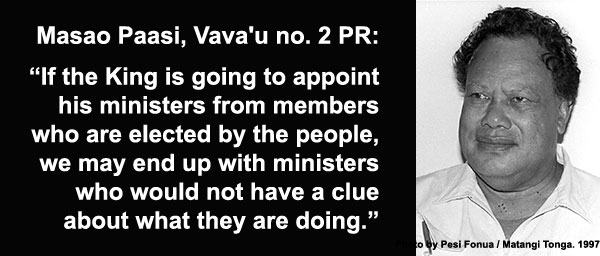

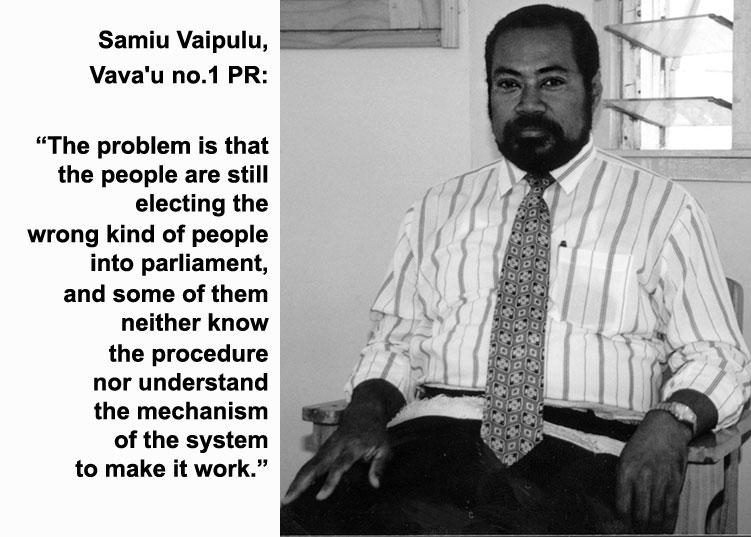

Meanwhile, the nine people’s representatives are divided on the issue of whether the King should continue to appoint the Cabinet ministers or whether they should be elected by the people. Both of the Vava’u People’s Representatives, Samiu Vaipulu and Masao Paasi prefer that the King appoints his ministers from the community at large.

Masao Paasi, the longest serving member of Parliament, who first entered the House in 1966 at the age of 29, said that Tonga is too small, “and it is better for the King to have more people to choose from. If he is going to appoint his ministers from members who are elected by the people, we may end up with ministers who would not have a clue about what they are doing.”

However, Masao expressed his concern over ministers whom he believed had been in their posts for far too long. “To bring some fresh blood into the system, and to keep the ministers on their toes, I think their term in office should be limited to three or five years.”

“The other alternative is for the ministers to stay out of parliament, because it is a conflict of interests for them to be in parliament where the rules and regulations relating to the executive are decided, but then they are the executive. They are actually drafting their own rules,” he said.

On the issue of whether the House holds any authority to tell Cabinet Ministers what to do, Samiu Vaipulu pointed out that it had been clearly stipulated in the Constitution that, “the people’s representatives may table bills, pass resolutions, and impeach Cabinet ministers. The problem is that the people are still electing the wrong kind of people into parliament, and some of them neither know the procedure nor understand the mechanism of the system to make it work.”

Masao Paasi is one member of parliament who has tabled bills into the House. The first one by an elected member in 1996 and a second one this year. Masao has also tabled motions for impeachments, which were passed by the House, two against Cabinet Ministers and one against a Chief Justice. His latest attempt to impeach the Minister of Justice, the Hon. Tevita Tupou, this year was annulled by the House in the final Hour.

To impeach a cabinet minister or a judge, a member must first present a motion of impeachment to the House, and if the motion is passed then it proceeds on to a hearing. Most motions of impeachment, are rejected by the House in the first instance.

House Resolutions have not been successfully put into practice, and Masao said that the reason is a longstanding attitude problem, “for years Cabinet Ministers were the only members of House with a decent education, and therefore were supposed to know what was best to be done. It was taken for granted that they knew better, and therefore the house could net tell the Cabinet what to do, so a resolution from the House is much the same as a motion. It is passed by the House and then it goes to Cabinet for their deliberation, and in most instances it ends there”.

Masao sincerely believed that something should be done to upgrade the work of the House. He said that debates in the House were a useless exercise because in the end which ever side the ministers voted for would win, “it is only natural for the noble’s representatives to take sides with the ministers, for two reasons. Firstly, some of the ministers hold hereditary noble titles and at election time they voted for some of these noble’s representatives, so when we are voting over an issue that is very important to the ministers, it is only natural for a noble to vote with the ministers,” he said.

Put aside

“Secondly to that there is an attitude problem. In the past the only members of the House with a decent education were the ministers, and the nobles traditionally always agreed with them because they were the educated ones. But things have changed and we now have elected representatives on the noble’s and the people’s tables with university degrees, so debating is becoming very aggressive, but at voting time all the good points are just being put aside.”

The other seven people’s representatives, ‘Akilisi Pohiva, Mahe Tupouniua, and Viliami Fukofuka, from Tongatapu; ‘Uliti Uata and Teisina Fuko from Ha’apai; ‘Aisea Ta’ofi from the Niuas, and Tu’ipulotu Lauaki from ‘Eua, are more united in their desire for more democratic change to the Tongan system of government. They have presented motions calling for the introduction of the Westminster style parliamentary system to Tonga, and when this motion was rejected by the House they launched another motion for all the members of the House to be elected by the people, then for the King to appoint his ministers from them. This motion was also rejected from the House.

‘Akilisi Pohiva believed that the King would still have an ample number of capable elected members to choose from if the people elected all the members of parliament, “there are too many educated people here, and even people who have passed their New Zealand School Certificate examination can do the job.” Akilisi said he had tried to change the system, and his proposals had always been rejected by the government, so his latest approach was to bring in constitutional experts from overseas to draft a constitution which he would present to government, “accountability is my main concern.”

‘Aklisi believed that allowing the people to elect all the members of parliament was one fundamental move that Tonga must make, “I can’t see any other way around it, the force from outside is too strong. Democracy is very much a part of the globilization of the world economy and we have to be a part of it.”

With regard to the fact that Tonga is the most stable government in the region, ‘Akilisi said that Tonga’s stable government was not of its own making, but was the result of an economy that had been propped up “with aid money and remittances”. ‘Akilisi said that if these two sources of foreign earnings were stopped it would be a test to the Tongan government, “and I don’t think it will remain stable.”

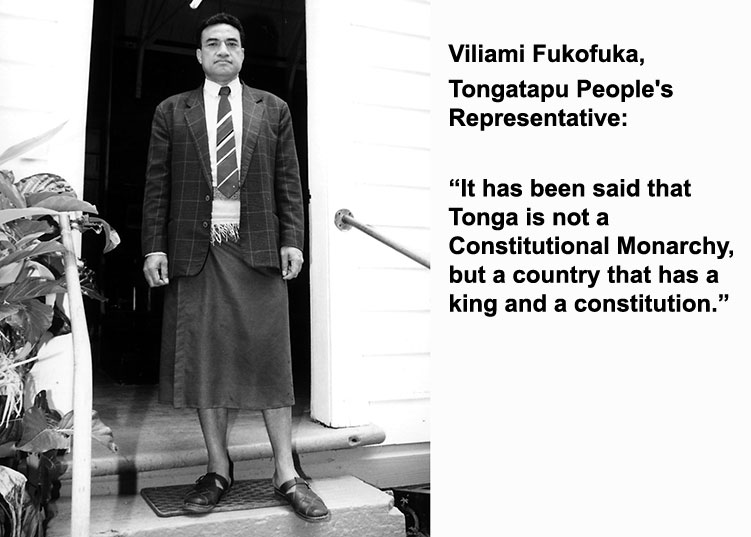

Viliami Fukofuka, the Tongatapu no. 3 People’s Representative, would like to see some changes to the Constitution and he said he was proposing that the King establish a Royal Commission to review the Constitution. Viliami was an active member of the so-called Pro Democracy Movement, and later became a member of the now defunct People’s Party.

He expressed his disappointment with the decline of the Pro Democracy Movement. “It was based on a few individuals, and when they lost interest it collapsed.”

Viliami still wanted to pursue the concept of political parties, and he wanted to go on and form a political party in the near future, “ I would like to see more people participating in the decision making process of government.” He predicted that a major political change would take place within the next 10 years to 20 years.

One area of great concern for Viliami is the lack of formal control in the decision making process of Government. “Take the civil service for example, if someone is dismissed form the service, he has to appeal to the same people who appointed, and then dismissed him. So right through the public service there is no checking mechanism. There should be a Tribunal Commission and the Auditor should be given wider power. It is back to accountability,” he said.

The nobles who have been labelled as the powerbrokers in the House, in general are not supportive of the move by some people’s representatives to make fundamental changes, including the prospect of being elected to the House by the people.

Hon. Tu’ivakano, the Tongatapu no. 3 Noble’s Representative said that it was important to clarify whom they are representing in parliament, “we are in the House to represent our Kaingas, the people who live in our estates, and our vote on issues in the House is based on what we think is best for the people, and the country as a whole.” Tu’ivakano stressed the importance of their position in the House, because the nobles can reject bills and motions if they are not for the advantage of the people, and the country.

With regards to a motion that was presented to the House, calling for the reinstatement of the impeachment case against the Minister of Justice, and for noble’s representatives to be elected by the people. Tu’ivakano thought that the motion was in response to the support they gave to the table of the ministers which annulled the case that was tabled by the nine people’s representatives. Tu’ivakano stressed his belief in a statement made by the King Taufa’ahau Tupou IV, saying that parliament was similar to the gathering of a family to meet and to decide what was best to be done for the whole family. “We are not there to have an argument, but to have a constructive discussion. The House is not run along political party concepts, as some members are trying to make it to be. They have to be very careful because if it is misinterpreted we could go back to before 1875, when there was a lot of bloodshed. A lot of people are not supporting what they are trying to do.”

Keep identity

Tu’ivakano believed that a few changes need to be made to the Constitution, but more important was the need to the Constitution, but more important was the need to address some of the social changes that are taking place because of people going overseas, and the impact of television. We should bear in mind the kind changes we would like to see taking place, he said, “it is important for us to keep our identity. We have something that other Polynesian people would like to have. The Hawaiian, Maoris, and others are trying to revive their culture in a hope of becoming like us.

“Our way of life evolved within the extended family, we can’t live the individualistic lifestyle of New Zealanders, and we have witnessed this during some of our cultural events, such as marriages and funerals.” Tu’ivakano said that there were a number of social changes that Tongans accepted, but really they were imported behaviours. “In the past brothers and sisters did not live in the same house, but now they do. When we sit down to watch television, the whole family comes to one room. What was tapu is no longer tapu, and therefore our respect for each other is eroding. I think we should go back to that, because it is the only way we can keep our way of life, where respect plays a very important role.” Tu’ivakano also stressed the important roles played by the Christian churches.

‘Eseta Fusitu’a, the Deputy Chief Secretary and Deputy Secretary to Cabinet explained the importance of the cultural relationship between the people of Tonga and their king to the force of government, “it is a contributing factor to the effectiveness of government. You take the King, because of his socio-kingship relationship with the whole Kingdom his authority as King of Tonga far exceeds his authority in the Constitution. Ninety per cent of the King’s authority is not in the Constitution, it is in the culture,” she said.

“Have you ever seen a crisis being solved by politicians? No politician can exercise that authority – the people will ask: what right have got to address us? When we have a crisis like the Toloa-‘Atele crisis (students from a government school and church college fought and a dormitory and gardens were destroyed), it is our cultural leader who will go there and address them, and his authority is accepted. The power for the King stands on two feet, whereas the political leader in, say New Zealand, stands on only one foot, it lacks the cultural base.”

The Tongan procedure of choosing its political leader is a process that has been by other Pacific leaders. Ratu Sir Kamasese Mara, in an interview in 1991 said that the Tongans had perfected a system where their leaders are carefully selected, “even before they are born, and are raised from the day they are born to become leaders. Unlike the elected system of government where political leaders are elected from just any member of the community.”

Temptation and corruption

‘Eseta believed that an attractive thing about elected government was the presumption that there is greater accountability, “but unfortunately because it is an elected government, there is the temptation to grab as much as you can get before your tenure is over, and that is a built-in problem of elected governments,” she said. She believed that an elected system builds circumstances of temptation and corruption.

“One thing that we should be proud of is that we have a stable government, and that is no small success for a small island nation in a turbulent world. We have an uncorrupt government, and I have no hesitation in saying that. Government that has made errors, yes, but not corruption. When you look at those factors they constitute the fundamental roles that any government can play.

“Look at how our ministers are appointed, compared to an elected government where you are appointed as a minister first of all after being in the good books of the party’s leader. In order to be on the good books of the party’s leader that is when corruption usually take place. Take a look at our system, there is no such relationship between the king and the person who becomes a minister. In Tonga the person suddenly learns about it when he receives an invitation from the palace to become a minister, there is never any warning. He has not had to tow the line with the King. He has not had to do favours for him as a party leader, he has not had to do favours for the Cabinet. Suddenly he becomes a minister. So the typical circumstances where the political corruption evidently is committed, do not occur here.” ‘Eseta said that when a person became a minister by the direct Royal appointment, theorectically speaking, he did not have to do favours for the Prime Minister, they did not have to do favours for each other, and then because of the system, the ministers run 95 per cent of the government. There is only five per cent or less of government matters, which the law directed must go to the Privy Council where the King was then directly involved, she said.

“The minister having done no politicising to anybody becomes a minister, and when he becomes a minister he does not even have to tow the line with the king all the time,”

The proclamation of the Tongan Constitution was an outstanding achievement made by Tupou I. It elevated the Tongan monarchy into a nationhood status recognised by the European powers of, France, Germany and Britain, and saved Tonga from their quest for territories in the South Pacific. Countries that did not have an established form of government were easy prey. ‘Eseta said that Tonga alone in the South Pacific was fully developed politically when the colonisation of the Pacific began. “When the Europeans came to the Pacific only Tonga had completed its political evolution, we already had 1,000 years of a single nationhood, and a single ruling hierarchy. In the case of Samoa, it had evolved to having four paramount chiefs. In the case of Fiji it had got nowhere. So neither in their distant memory nor in their recent history have they ever had single nationhood, and a single head of state. For all of our neighbours, and therefore, our concept has to be different from our neighbours, and therefore our concept has to be different, because we have achieved what nobody else has done.”

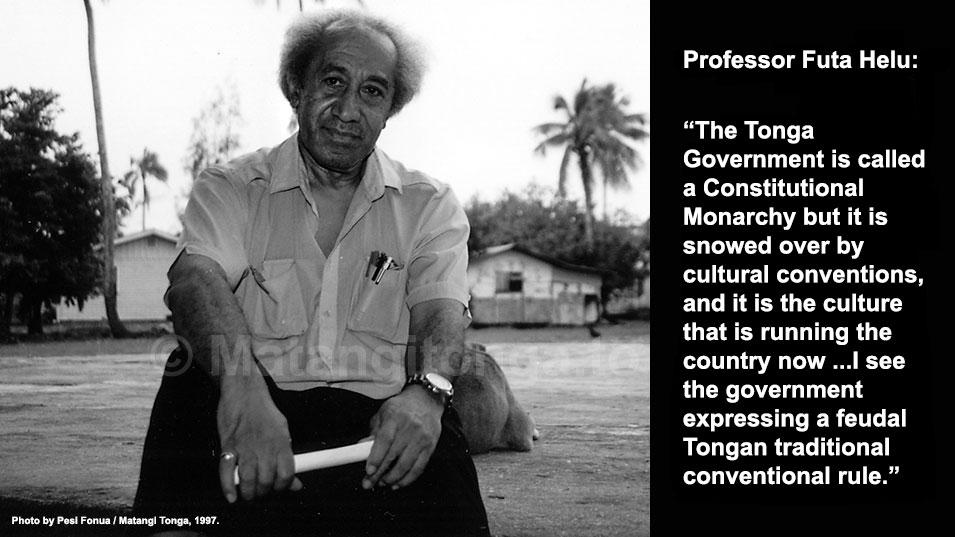

Professor Futa Helu, one of Tonga’s most active political thinkers, who labels himself as “a little liberal or a small democrat”, believed that the one most important political step for Tonga to take at this point of time was, “for the governed to have a hand in choosing their governors.”

He said that the question of a constitutional monarchy was not an issue of importance because, “everyone is engaged in a class war, a war between the traditional privileged classes and the commoner classes. The Tonga government is called a constitutional monarchy but it is snowed over by cultural conventions, and it is the culture that is running the country now,” he said.

“I don’t see government expressing a constitutional monarchical situation here. I see the government expressing a feudal Tongan traditional conventional rule. The label constitutional monarchy is a misnomer. Instead, it would be very close to absolute monarchy.

“It is a monarchy that is backed by a strong aristocracy. I see Tupou I in one way weakning the nobility, that was one aim, and strengthening the Tu’I Kanonupolu which was still weak at the time, and I appreciate that, but it has hin the course of a century or so given all power to the Tu’i Kanokupolu, and the Tu’i Kanokupolu has netted in the nobility to become a supporting base for its power. The nobility is doing this for self-interest because they see that as a means of holding onto power themselves,” Futa said.

“I think Tupou’s I sentiment was to slowly attain a true constitutional monarchy, but it has worked out somewhat differently."

Landed lords

“In the case of Europe the transition from feudalism to capitalism and then to constitutional monarchy to place because a business sector was slowly built up, and it became separated from the landed lords. There was a kind of confrontation and the business sector then went on to build towns and trading centres, and cities, and so the landed gentry, lords, and aristocracy was weakened because of this separation of power. Capitalism took its rise from the segregation of a moneyed class from a landed class, this does not seem to happen here, I see that the landed class in Tonga is moving onto the business sector and taking over that sector also. So I think the common class will remain where they are.”

Futa said that a solution that could be introduced at this point of time was for the governed to have a hand choosing their governors, “right now the governed do not have a hand in choosing their governors, and that is something that has to be considered. If we want to experiment with parties, I think it is something that we can do but I think we have to be very careful in introducing parties, and we must make it legally binding that we have only two or very few parties, but not to throw it open for everyone to have its party, because this small society will become so fragmented,” he said.