In the field of ancient DNA remarkable new insights for Oceanic settlement are being revealed. The Lapita migration across Oceania was rapid, and undertaken by a homogeneous group both culturally and genetically. Arriving in Tonga almost three millennia ago, it marks the birth of Polynesia.

By David V. Burley and Geoffrey R. Clark

It is an exciting time to be an archaeologist! Scientific breakthroughs in several areas are providing innovative tools to discover, document, date and analyze materials from the long distant past. Nowhere is this more apparent than in the field of ancient DNA where remarkable new insights for Oceanic settlement are being revealed.

Ancient DNA revolution

Unlike modern DNA from a living person, ancient DNA is decayed and fragmented, broken down by age and environment. DNA in archaeological samples has been recognized for some time, but the technology to decode the smaller bits and pieces proved inadequate. That circumstance radically changed in the past decade with development of high throughput, next generation sequencing. Knowledge of the human past on a global scale is being transformed accordingly.

Historical narratives are furiously being rewritten through the lens of DNA, in some cases going back tens of thousands of years. From a decoding of the Neanderthal genome of 40,000 years ago, we learn that our Homo sapien fore-bearers interbred with this long extinct species. No more than a finger bone excavated from a cave in Siberia provides genetic data for the Denisovans, an entirely new species on the human family tree.

Critically important to archaeologists, ancient DNA tracks the migration of people over great distances with reasonable degrees of certainty. A focus on the ancient DNA of Oceania, and what it can tell us of settlement and the interaction of peoples across this vast expanse, is hardly surprising.

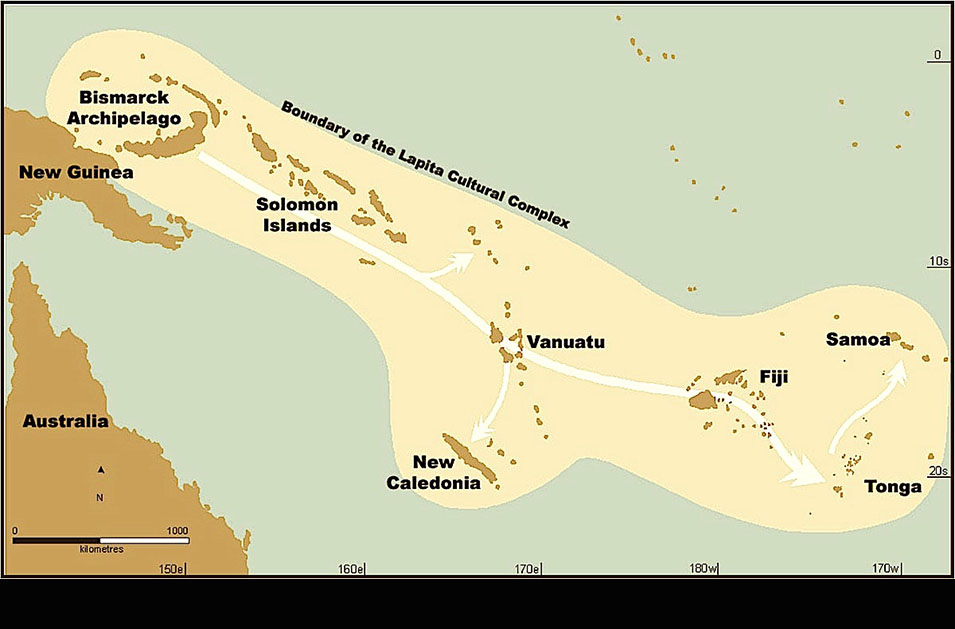

Paradox in Oceanic settlement

A previous article in Matangi Tonga provides insights into Tonga’s initial settlement, including the arrival of the first canoes 2850 years ago. These are the Lapita peoples, characterized by a distinctive type of decoration on their pots. Lapita ceramics mark a colonisation trail, one beginning in the Bismarck Archipelago off north coast New Guinea, running through the eastern Solomon Island outliers into Vanuatu and New Caledonia, and extending even further east into Fiji, Tonga and Samoa.

Linguists identify the language of this migration as Austronesian, a language family with origins in island southeast Asia between 4000 and 5000 years ago. With Tonga at the far eastern end of this diaspora, and with no archaeological evidence for later migrations, it stands to reason that Lapita peoples were Polynesian-like in appearance. Yet the peoples of Vanuatu, New Caledonia and Fiji are quite different in constitution, in spite of the same Lapita ancestry, and in their speaking of Austronesian languages. This Polynesian/Melanesian divide forms a paradox, one debated by archaeologists for a half century or more.

Answer buried at Teouma

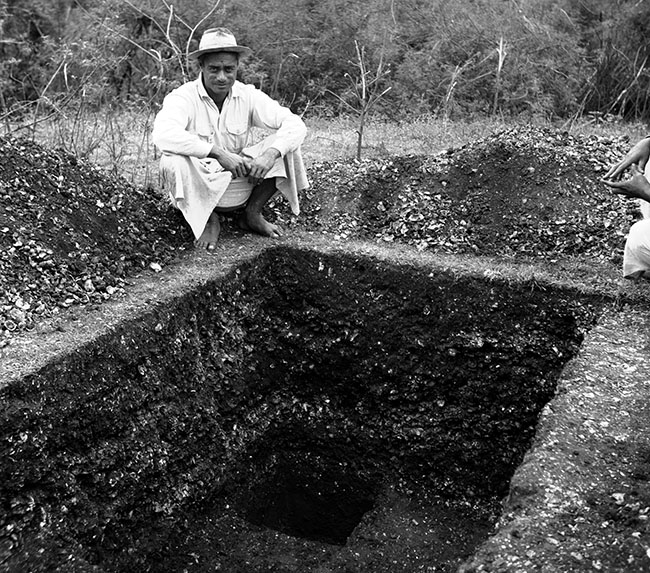

The expansion of a prawn farm in 2003 at Teouma on Efate, Vanuatu accidentally encountered one of the more spectacular discoveries in Pacific archaeology, a Lapita cemetery. Lapita burials are rare, and the over 100 individuals eventually excavated from Teouma provide unique insights into funerary and ritual practices associated with the dead. To say these practices are strange seems an understatement, at least from a western perspective. The interment of a skull within an elaborately decorated Lapita pot, curiously missing limb bones from individual skeletons, and one burial where additional skulls were meticulously placed across its torso brought international attention.

Beyond the macabre, the hidden value of the Teouma skeletons was their reflection on health, diet, disease and physical features for the Lapita colonizing group. With the approval of nearby villagers in 2014, Teouma bone samples were analyzed for DNA in a Harvard University lab in the eastern United States.

Successful sequencing of the DNA was limited to three of the samples. The results were extraordinary nevertheless. The Teouma DNA was far more similar to modern samples from southeast Asia and the Philippines than it was to ni Vanuatu peoples today. Additional analyses of more recent skeletons and their interpretation identify a second migration into Vanuatu, one where Lapita peoples were replaced or incrementally absorbed into the migrant group between 2500 and 2300 years ago. These migrants were Papuans, people from western Melanesia whose antiquity in the Pacific extends to 40,000 years at the least.

Tongan burials at Talasiu

On the outskirts of Lapaha at Talasiu is a late Lapita site, first identified a century ago by archaeologist Thomas McKern. A gravelled road running from the highway to the lagoon edge has exposed shell, pottery fragments, umu rock and occasionally, as the case in 2008, human bone. With grading and a widening of the shoulder about to take place, a project was mounted quickly to recover whatever information might be gained. That project encountered the earliest known cemetery in Polynesia, one dating between 2700 and 2600 years ago.

Additional projects have been undertaken at Talasiu and these provide information on both the people who lived at the site, and their funerary practices. The removal of skulls and select long bones from several of the burials are similar in respect to Teouma. Also like Teouma, initially recovered samples were sent for DNA analysis, in this case to the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History in Jena, Germany. Two were successfully sequenced, one from a man and the other from a woman.

Comparative analyses of the Talasiu DNA highlights the ancestral relationship of these late Lapita individuals to contemporary Tongans. This fits closely with what we know from the archaeological record. Equally discerning, and strikingly significant, the Talasiu DNA has an even closer match to the Lapita burials at Teouma, similarly falling within the contemporary profile for southeast Asia.

The Lapita migration across Oceania was rapid, and it was undertaken by a homogeneous group both culturally and genetically. Arriving in Tonga almost three millennia ago, it marks the birth of Polynesia.

An afterword of caution

Our account of the DNA story in Oceania is based on interpretive threads extracted from two key publications in 2018. These papers provide a dense morass of data, technical accounts of methods, and high-powered statistical analyses in support. The articles and their conclusions are not without criticism.

The most consistent question, and one that should be obvious to the reader, relates to sample numbers. Can we really construct a history of such magnitude from the ancient DNA of so few people? On the one hand, DNA leaves little room for debate relative to the individuals it was drawn from. Additionally, the results are not presented in isolation but compared against a larger archive of more recent and contemporary DNA. On the other hand, as one critic opines, what if the Lapita migration was undertaken by a heterogeneous population of Austronesian and Papuan peoples? Five individuals from Teouma and Tonga might represent only one of the sides in a very complicated story.

- Dr. David V. Burley is a Professor of Archaeology at Simon Fraser University in Burnaby, BC, Canada. He has carried out archaeological studies in Tonga since 1989.

- Professor Geoffrey Clark is an archaeologist at the Australian National University in Canberra. He has worked in Tonga for 15 years, especially on the conservation of the Lapaha langi. He has supervised the Talasiu project with Frédérique Valentin since 2008.

--

More articles in this Matangi Tonga series on pre-history:

- Ha'apai rock art suggests Hawaiian link about 1400-1600AD

- Tongatapu's astonishing burial mounds

- Giant Tongan fruit-gulping pigeon eaten into extinction

- The last Fale 'Otua in Ha'apai

- 'Ata and its archaeology

- The Lapita origins of Tongan ngatu and design

- Scarcity in Paradise

- Early settlement of Ha‘apai brilliantly laid title to islands

- Taupita –Tonga’s earliest known game

- The first Tongans