By Shane Egan and David Burley

The beach and lagoon at Houmale‘eia on the north end of Foa Island in Ha‘apai is a spectacular place. Now home to Matafonua Lodge, its ancient history came vividly to life in 2008 when Australian visitors inadvertently discovered a kaleidoscope of images carved into a beach rock surface.

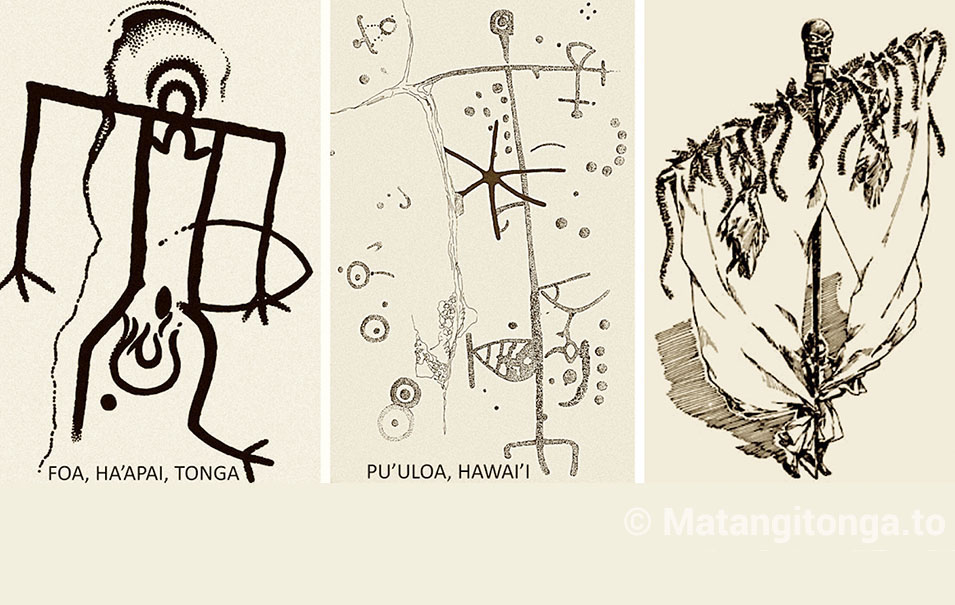

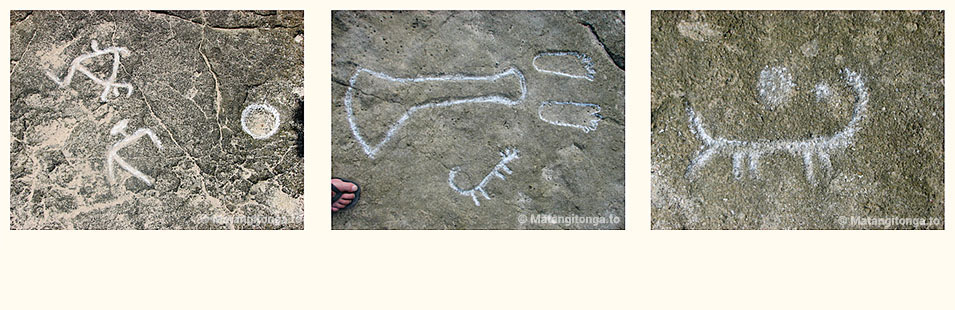

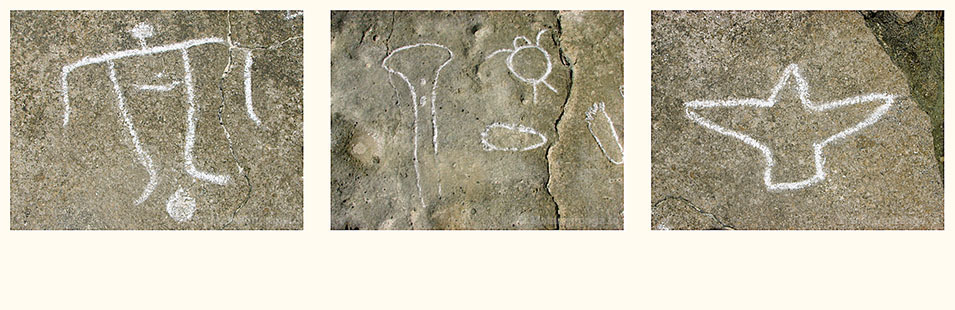

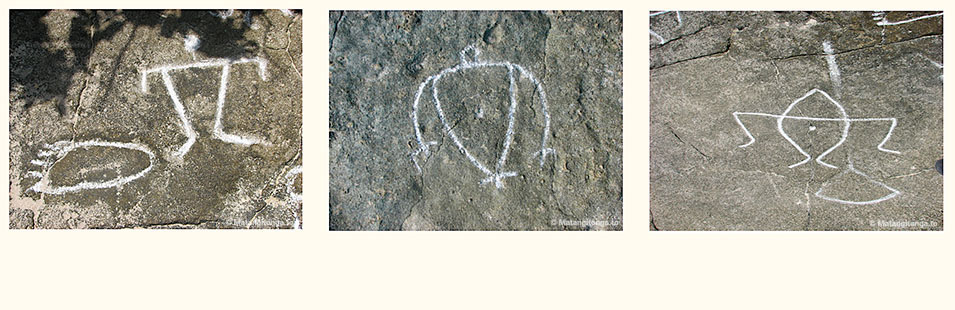

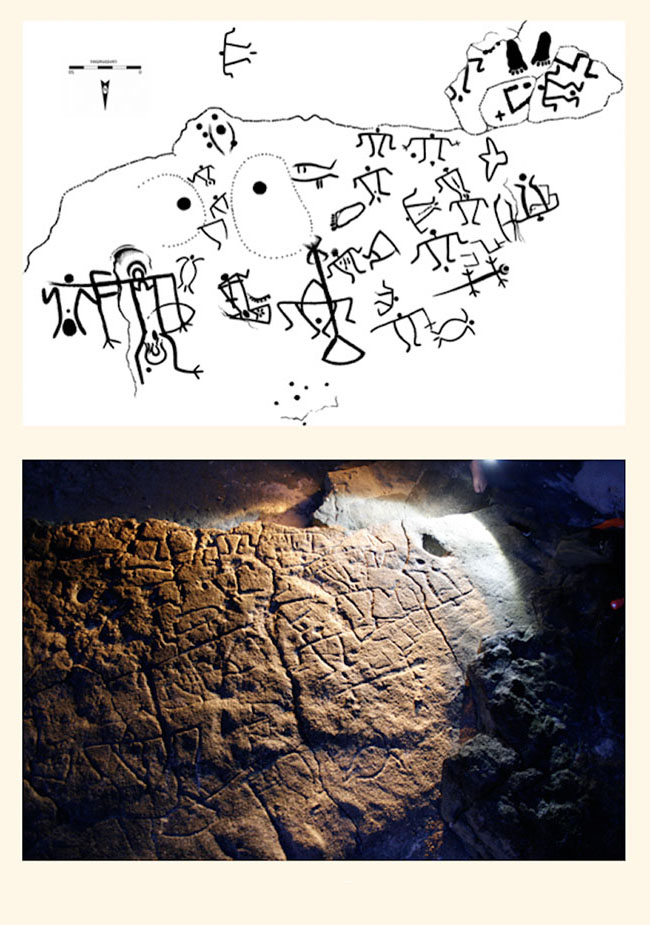

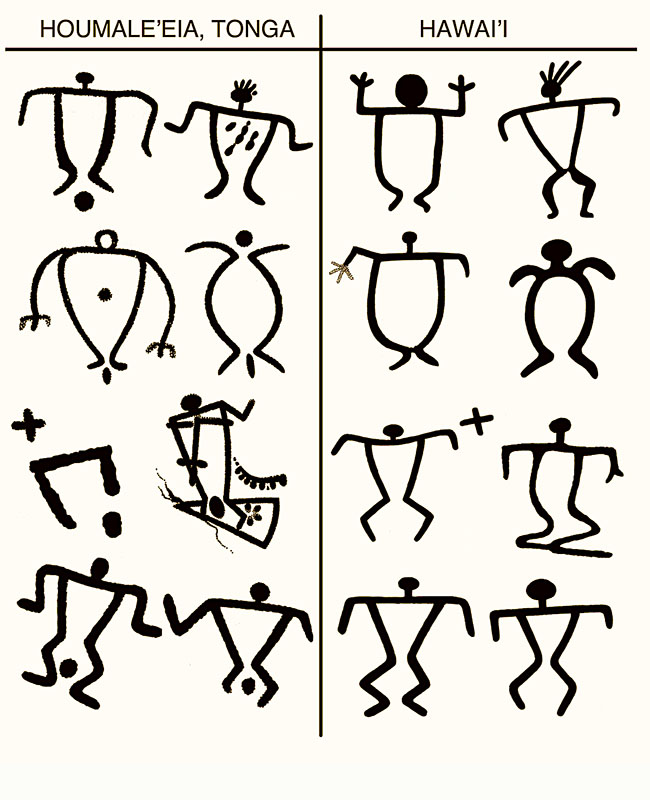

Human feet, triangular bodied people, lizards, dogs, turtles and other representations hinted astoundingly at a Hawaiian connection. We recorded the site in detail. A report in Matangi Tonga Online fuelled international media interest at the time.

The Hawaiian link to the images at Houmale‘eia is difficult to debate. Rock art in Hawaii is wide spread through the islands. It was initiated not long after Hawaii was first settled in the 12th century AD, and it continued into the early historic era.

Other than Hawai’i, and with exception of Ha‘apai, this type of rock art occurs nowhere else in Polynesia as an integrated tradition with the full suite of depictions. The artwork of Houmale‘eia could as easily have been documented on the lava flows of Ka’ūpūlehu or Pu’uloa on the big island of Hawai’i without an eyebrow being raised.

Was the artist a Hawaiian visiting Tonga, or a Tongan who had visited Hawai’i and brought the tradition home? We cannot be sure.

(In the following images the rock engravings have been highlighted in chalk by the photographers.)

What we can say is that aspects of the art at Houmale‘eia suggests discrete cultural knowledge where symbolic elements are being expressed. The integration of cupules (cup-like depressions), the application of a distinctive headdress, the possibilities for a poi pounder, or the use of transformational images provide subtle hints of the artist‘s origins.

One representation in particular stands out. It is an image with tell-tale traits identified in Hawaiian rock art with the god Lono. Celebrated annually at the Makahiki festival, he is the god of fertility, peace and rebirth of the land. The broad shoulders, small circular head and lengthened body portray the akua loa. This was a staff and banner in the likeness of Lono, an icon carried around the island during the four-month celebration in honour of the god.

Age of Houmale‘eia

Freelance writer, Sione Mokofisi contributed another perspective to the 2009 Matangi Tonga Online report. Hawaiians, as he was to describe, were crew members on the Port-au-Prince when captured in Ha‘apai in 1806. Would they not be natural suspects for the carvings at Houmale‘eia? This is a logical possibility, though other factors point provocatively to an earlier era.

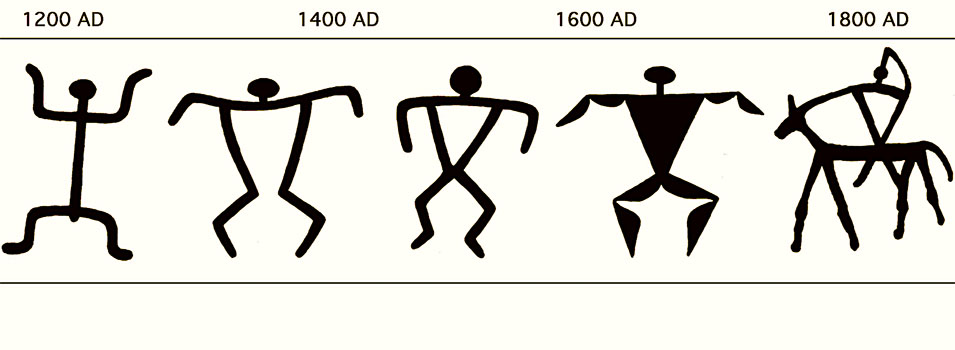

Hawaiian rock art is well-studied, with a stylistic chronology for human forms fully worked out. The earliest types are stick figures, carved not long after first land fall. These evolved into different forms with open and closed triangular bodies, the later types adding muscles. The most recent panels document clearly the arrival and impact of Europeans. Houmale‘eia figures fall into this typological progression in the middle part of the sequence, dating roughly between 1400 and 1600 AD.

We believe the mid-sequence date is supported by an event represented in the art at Houmale‘eia itself. A sia heu lupe employed in the chiefly sport of pigeon snaring occurs less than one hundred metres from the rock art panels. The portrayal of a large bird, a pigeon net, and a large congregation of people seems an apt depiction of this activity. Pigeon snaring as a sport was abandoned in Tonga by the end of the 18th century as chiefly conflict emerged and became widespread.

Artist in Ha‘apai

In 1929, Archaeologist W.C. McKern briefly described a rock art site with figurative images on Telekivava‘u in southern Ha‘apai. One of the images had a triangular body. As sketched by a cadastral land surveyor in 1957, the rock art panel is limited in scale but in keeping with the Houmale‘eia style.

A third Ha‘apai site has been discovered more recently on the small island of Luahoko, some 13 km northwest of Foa. Again, the scale is small but the glyphs are appropriate to the ones recorded on Foa. The artist of Houmale‘eia, it seems, was freely moving about in Ha‘apai.

Tombs at ‘Uiha and Lapaha

The Royal tomb of Mala‘e Lahi on ‘Uiha Island has the outline of a foot engraved into one of its beach rock facing stones to the side. The foot seemed out of place and enigmatic when first recorded in 1991. The image, we now believe, likely existed on the beach rock surface prior to it being cut and removed for tomb construction.

Three Houmale‘eia-like triangular bodied glyphs recently were discovered by Australian archaeologist Geoff Clark on the facing stones of Langi Tuoteau at Lapaha. The orientation and placement of these glyphs again indicates incidental presence on a beach rock exposure where stone was later quarried. Langi Tuoteau was constructed for the 35th Tu‘i Tonga, Tu‘ipulotu II. Its stones were quarried prior to the mid-1700s AD, long preceding the Port au Prince in Ha‘apai.

Long distance voyaging

The straight-line distance between Hawai‘i and Tonga is 5,000 km, a seemingly incomprehensible voyage in a double hulled canoe with mat sails. The sheer fact that east Polynesia was completely settled no later than 1350 AD indicates otherwise. The archaeological record is sparse in its documention of such inter-island voyages. Hawaiian connections to Tahiti, and Tahitian and southern Cook Island connections to Tonga and Samoa are suggested in the data.

A most compelling account for such voyages was presented to Captain Cook in 1769 by Tupaia, a Tahitian high priest navigator. He not only provided positioning data for a wide swath of islands he was aware of or had visited across Polynesia, but identified them by name. ‘Uiha was among these.

Stranger king

It is not uncommon for traditional societies to attribute or justify radical changes in social and political structures to visiting foreigners. Anthropologists speak to this as the myth of the stranger king.

In Hawai‘i, it was Pa’ao, high priest of Kahiki (Tahiti) who introduced religious and political reform in the 15th century. Pa’ao was a mariner of high repute, whose travels potentially included Samoa.

In traditional Tongan history, it is Lo’au who redefined social and political structures in the 12th and 15th centuries. Tevita Ka‘ili, Professor and Dean at Brigham Young University in Hawai’i, long has hypothesized Lo’au as Hawaiian. Perhaps he is right.

Dr. David V. Burley is a Professor of Archaeology at Simon Fraser University in Burnaby, BC, Canada. He has carried out archaeological studies in Tonga since 1989.

Dr. David V. Burley is a Professor of Archaeology at Simon Fraser University in Burnaby, BC, Canada. He has carried out archaeological studies in Tonga since 1989.

Shane Egan is an Australian artist who lives at Kanokupolu, where he established the Tonga Maritime Museum. He is a founding member of the Tonga Heritage Society, and supports archaeological studies in Tonga.

Shane Egan is an Australian artist who lives at Kanokupolu, where he established the Tonga Maritime Museum. He is a founding member of the Tonga Heritage Society, and supports archaeological studies in Tonga.

See also:

Ancient Hawaiian rock art discovered in Tonga

'Ulukalala's Hawaiians could be the ancient rock art carvers

More articles in this series:

- <a href="/%3Ca%20href%3D"https://matangitonga.to/2021/01/29/ancient-dna-provides-new-understanding-oceanic-settlement">https://matangitonga.to/2021/0½9/ancient-dna-provides-new-understandin...

- Tongatapu's astonishing burial mounds

- Giant Tongan fruit-gulping pigeon eaten into extinction

- The last Fale 'Otua in Ha'apai

- 'Ata and its archaeology

- The Lapita origins of Tongan ngatu and design

- Scarcity in Paradise

- Early settlement of Ha‘apai brilliantly laid title to islands

- Taupita –Tonga’s earliest known game

- The first Tongans