By Terence Wood

Although the Trump administration is now attempting to walk back some of the most obviously murderous aspects of its aid freeze, its ramifications remain: the damage already done, the effects on work still covered by the freeze, the apparent demise of USAID, the sheer capriciousness of the decision. (To make matters worse, supposed humanitarian exemptions to the aid freeze do not appear to be working.)

While impacts on other parts of the world have dominated the headlines, the decision is going to be felt in the Pacific too. The region is the world’s most aid-dependent. Its countries are, for the most part, either tiny and remote or larger and politically unstable. Malaria, HIV/AIDS, dengue fever and tuberculosis are major problems in several countries. Most Pacific countries are highly vulnerable to the effects of climate change and natural disasters.

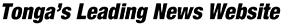

Regionally, the United States is not nearly as large a donor as Australia but Figure 1, taken from Lowy Institute data, shows it gave more to the region than China did over the five most recent years for which data were available for both countries. If the policy settings of the Biden administration had been maintained, US aid was set to increase under the first-ever US-Pacific Partnership Strategy, including through a pledge of $60 million per annum to the Forum Fisheries Agency and the relaunching of the Peace Corps in the Pacific.

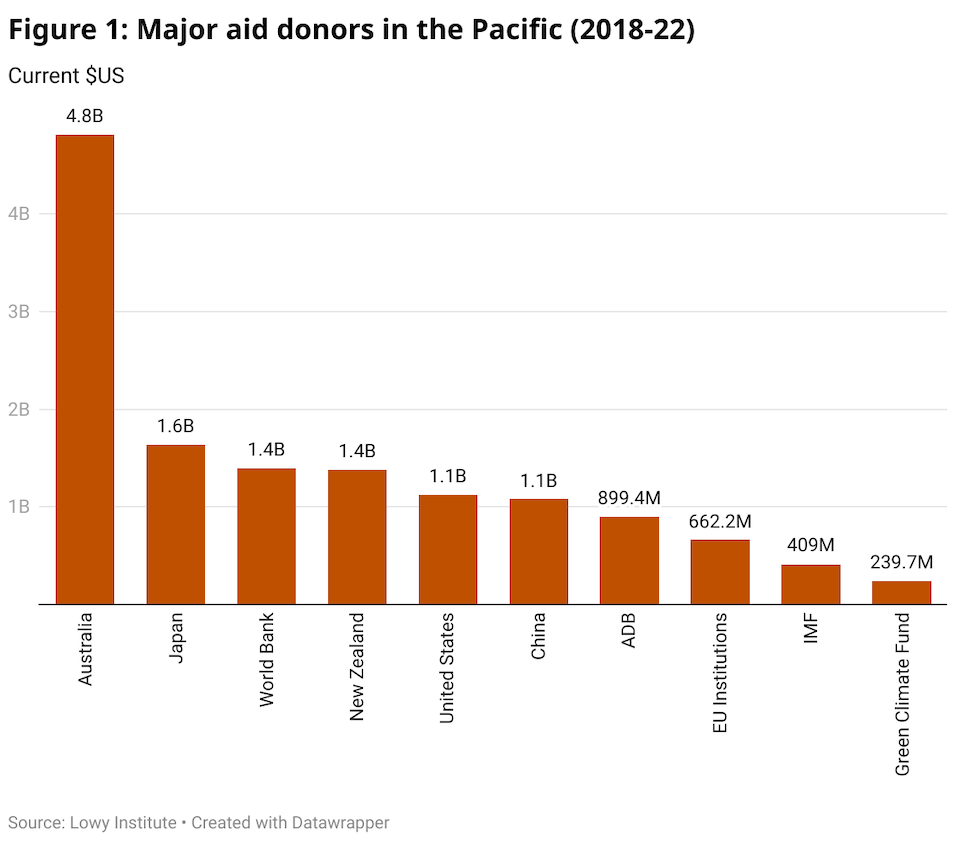

US aid is not equally spread across the Pacific. As can be seen in Figure 2 (based on OECD reporting for the five most recent years with data), the bulk of US aid to the Pacific goes to Micronesia, and in particular the so-called Compact States: the Federated States of Micronesia, the Marshall Islands and Palau.

As my colleague Cameron Hill has reported, there is considerable confusion as to whether aid to the Compact States is covered by Trump’s executive order to freeze US aid. Legally, it seems as if the compact states should be excluded from the freeze but in practice it appears as if impacts are being felt.

A cessation of most US aid would be disastrous for the Compact States, but that’s not the end of the story. In recent years the United States has provided more than US$13 million dollars in disaster preparedness support to countries such as Papua New Guinea, Solomon Islands, Vanuatu and Tonga. It has provided nearly US$20 million dollars in HIV assistance to Papua New Guinea and Fiji. (Some of this was funding through the US President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief, known as PEPFAR, which has been declared exempt from the funding freeze. However, the majority of the funding does not appear to have been from PEPFAR.) It has provided nearly US$12 million for biodiversity work in Papua New Guinea. It has helped with unexploded ordnance removal in Solomon Islands (the ordnance in question being left over from World War 2 and a perennial problem).

There will be other flow-on effects too: the US is the largest contributor to the World Bank’s International Development Association (the Bank’s concessional financing arm). And the World Bank is the third largest aid donor in the Pacific. The US has also, historically, been the second largest donor to the Asian Development Bank’s Asian Development Fund. The Asian Development Bank is a major donor in the Pacific as the Figure 1 shows. It would be unprecedented for the United States to renege on existing funding commitments to these multilateral development institutions, but precedent counts for little at present.

Other US decisions about multilateral organisations will also be felt through the Pacific. The United States was the world’s largest contributor to the World Health Organization in 2024-25. The Trump administration has announced it will pull the US out of the WHO, which will have a massive impact on funding. As Samoa’s Prime Minister Fiame Naomi Mataʻafa has pointed out, the impacts of falling WHO funding will be felt in the Pacific too.

To make matters worse, if other donors attempt to fill aid gaps caused by what the United States is doing elsewhere, they might potentially cut their aid to the Pacific.

In a purely quantitative sense not all Pacific countries will be that badly affected directly by the US aid freeze. But the flow-on effects of what is happening in the United States – the world’s largest aid donor – will reach the Pacific one way or another.

It’s easy to feel helpless watching the United States right now. It is worth remembering, though, that Australia and New Zealand (the largest and third largest bilateral aid donors to the Pacific respectively) can help. We could quite easily increase our aid budgets and focus these increases on helping Pacific countries cope with the current American trainwreck. We will need to help for other reasons too: the government of the world’s most powerful country is in complete denial when it comes to climate change, which will increase the need for our assistance even more.

Australia and New Zealand often talk the talk about being good neighbours to the region. In the coming years, as another of the region’s neighbours goes rogue, we are – more than ever before – going to have to walk the walk.

--

- This article appeared first on Devpolicy Blog (devpolicy.org), from the Development Policy Centre at The Australian National University.

- Terence Wood is a Fellow at the Development Policy Centre. His research focuses on political governance in Western Melanesia, and Australian and New Zealand aid.