While ample resources – and high hopes – are being invested in the race to develop a COVID-19 vaccine, policymakers and the public should be preparing for a scenario in which no silver bullet is possible. But even in that case, writes renowned infectious disease expert William A. Haseltine, there are strong grounds to believe that we can control the virus and its spread.

By William A. Haseltine

By William A. Haseltine

When it comes to ending the COVID-19 crisis, our experience beating back HIV/AIDS can teach us much. Above all, it was never clear during that earlier pandemic whether we could count on an eventual vaccine to be part of the solution. In our efforts to overcome today’s crisis, we would be remiss to forget this lesson.

During the early years of the HIV/AIDS crisis, I ran a laboratory at Harvard University, where we were researching the virology of the disease. Early observations showed that an HIV infection elicits an unprecedentedly strong response from both arms of the immune system – the B cells and the T cells. The body detects the threat posed by the disease, and it fights back as hard as it can, but fails. How, I wondered, can we create a vaccine that outdoes the best our bodies can do? It has now been 35 years, and we still don’t have an answer.

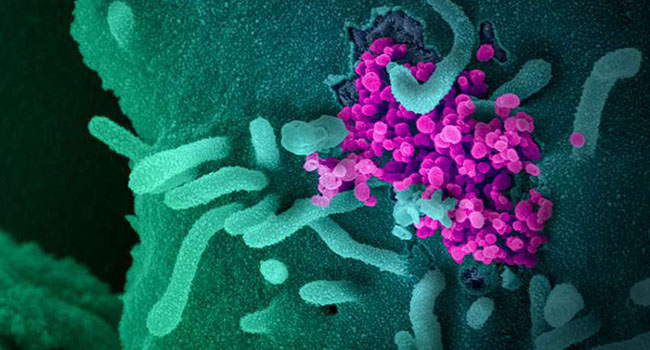

The quest for a COVID-19 vaccine isn’t this bleak, but nor is it particularly bright. Six decades of experience with coronaviruses – which cause the common cold as well as more serious diseases like severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) – offers reason for both optimism and caution.

Purpose of vaccine

The purpose of a vaccine is not to equip the body with an impenetrable shield that blocks all viruses from entry. Rather, a vaccine functions as an early warning system, alerting the body to the presence of foreign invaders and mobilizing its defenses. This rapid immune response is what clears the virus from the body before it can wreak havoc.

Although most people who develop an infection from a coronavirus (whether a feeble or potent variety) can overcome it, the exact process by which this happens remains unclear. It is a mystery, for example, why some people are able to rid themselves of an infection without any apparent help from antiviral antibodies. And even more puzzling is the fact that the same coronavirus that gives someone a cold one year, can return to haunt that person the following year.

The COVID-19 virus, SARS-CoV-2, seems to fit this pattern. Several studies have already found that the protective antibodies developed by the body in its fight against SARS-CoV-2 tend to fade quickly, leaving the door open to reinfection. This finding implies that achieving so-called “herd immunity” against the coronavirus is more of a fantasy than a realistic possibility.

As with HIV/AIDS, we are forced, once again, to ask whether we can do nature one better. Years of trying to develop a vaccine against SARS and MERS, and the experience so far with COVID-19 vaccines, suggests that the best we can hope for is partial, perhaps transient protection.

Change behaviour

But even if we are unable to produce effective COVID-19 vaccines, we will not be defenseless. As in the case of HIV/AIDS, we have a two-pronged fallback strategy: deploy the tools of public persuasion to modify behavior, and develop drugs that treat and prevent infection.

This strategy reduced the toll of the HIV/AIDS pandemic dramatically. Around 1.7 million new infections still occur each year, but that is far below the rate that originally drove the number of deaths above 50 million. Whereas an HIV diagnosis used to be a near-certain death sentence, effective combinations of anti-HIV drugs have transformed the disease into a chronic condition that can be managed for a full lifespan.

The first ingredient is behavioral change. Public-health campaigns against smoking and drunk driving have taught us that modifying human behavior is difficult but entirely possible. Combined with a limited period of mandatory social distancing, efforts to encourage responsible behavior – wearing masks, avoiding large indoor gatherings – could go a long way toward controlling COVID-19.

Drug treatments

As for the second ingredient, drug treatments, we now know that anti-virals can successfully control an epidemic, even when its causative agent is as subtle and persistent as HIV. The first success in HIV treatment came three years after the discovery of the virus, with the approval of zidovudine, a failed anti-cancer drug that had been discovered 20 years previously.

Within months of its initial success in the lab, zidovudine was proven to reduce virus levels in AIDS patients. This led to the very first remissions for patients in what had been, up to that point, a relentless progression toward death. But owing to the development of zidovudine-resistant strains of the virus in nearly all patients, relief proved short-lived.

Like HIV, cancers are persistent diseases that rapidly develop resistance to single drugs. So, to combat resistance to zidovudine, I proposed that we use a combination of anti-viral drugs against HIV, drawing on my previous experience as chair of the Division of Cancer Pharmacology at Harvard’s Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, where we developed new drug combinations to treat patients.

My laboratory started hunting for new features of the virus to target with additional anti-HIV drugs. The sequence of the HIV genome immediately revealed a wealth of opportunities. ...Since then, more than 25 drugs have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of HIV/AIDS.

Finally, I suggested that anti-HIV drugs might be effective in preventing infection if attempts to develop a vaccine failed. This concept is not new. Drugs can and do prevent infection by the malaria parasite, and monoclonal antibodies protect infants from infection by respiratory syncytial virus, another virus for which no vaccine exists. Such regimens require that drugs be safe and convenient.

Breakthroughs for HIV/AIDS

Recently, two independent breakthroughs brought this dream closer to reality for HIV/AIDS. ...

On July 1, Gilead Sciences published a paper in Nature that is destined to become a classic in the annals of drug discovery. A tour de force of science and medicine, the study demonstrated that an entirely new class of anti-HIV drugs, the anti-capsid drug GS-6207, has the potential to protect people from infection for up to eight months with a single injection. Gilead’s work is based on extensive prior research into the role of HIV capsid proteins. ... In fact, GS-6207 is the most potent anti-HIV drug ever discovered. It inhibits all naturally occurring HIV-1 strains tested and is active against HIV-2, as well. ...This drug is a potentially transformative tool in efforts to end the global HIV epidemic....

COVID-19 pandemic

Frightening as the COVID-19 pandemic may be, we must not ignore the experience we have gained from our multi-decade struggle against HIV/AIDS. That experience counsels against despair, even if a vaccine fails to live up to expectations.

If the best vaccine that we can get turns out to be short-acting and only partly effective, a strategy combining behavioral change and anti-viral drugs will still offer hope – I would even say certainty – that we can treat, cure, and prevent SARS-CoV-2 infections. As we speak, monoclonal antibodies and drugs that target specific viral proteins are making their way through the clinical-trial process, and additional candidates are emerging almost weekly from laboratories around the world.

Success against HIV was made possible by continuous and sustained policy support and decades of generous funding from governments and the pharmaceutical industry for basic and applied research. As long as such commitments are maintained, we will succeed against COVID-19 as well.

This article has been abridged. For full text see: Project Syndicate

William A. Haseltine a scientist, biotech entrepreneur, and infectious disease expert, is Chair and President of the global health think tank ACCESS Health International.

More articles: Forbes – William A. Haseltine