From Matangi Tonga Magazine Vol. 17, no. 2, August 2002.

How does Tonga’s law treat young offenders while protecting the Rights of the Child?

Matangi Tonga discovers that Tonga’s children are exposed to the full extent of adult punishments —from whippings to incarceration, while the youngest offenders might suffer both before being isolated from society and taken to serve long terms on a tiny offshore prison island.

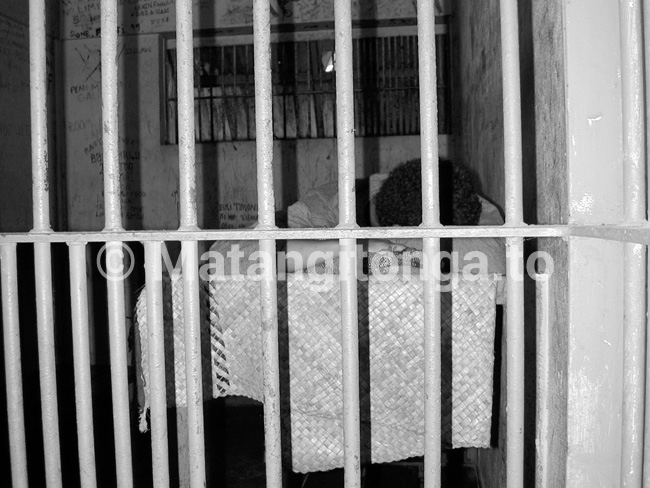

Did you know that Tongan law allows a child, as young as eight years old, to go to jail—in the same prison as adults—and face the same prison sentence, do the same prison work, and face the possibility of psychological, physical and sexual abuse by older inmates.

Did you know that around 70 per cent of offenders who go through the Police Magistrates’ Courts are aged in their teens to early 20’s?

Did you know that a heinous moral crime like the publication of child pornography is not punishable by domestic law?

These are all fact under the current laws of Tonga, implemented to protect the people of this country, and particularly the ones who are most vulnerable—our children.

Seven years ago, Tonga ratified the Convention on the Rights of the Child, and in that, Tonga as a nation, faces a behemoth task in implementing reform— a reform to abate youth crime and at the same time to provide the infrastructure much needed to safeguard children’s rights. A child is defined as being under 18 years old and their Rights include the right to education, and to safety.

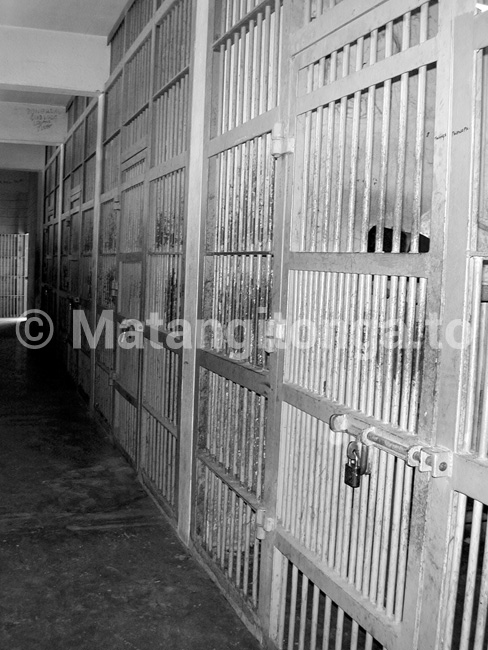

One of the major concerns for the Judiciary in most South Pacific countries, like Tonga, at present is the fact that there are no special facilities for juvenile offenders.

Right now there is a 14-year-old boy serving a three-year prison sentence, for housebreaking, and he’s done a year already. Incarcerated along with him are eight young teens under 16-years-old. The Superintendant of Prisons, Moleni Taufa, confirmed that, “just under 20” teens aged between 12 and 16 years old had done time in the last 12 months.

Matangi Tonga followed up the cases of some of these children and discovered reports of a horrifying accident to a jailed teen who suffered disfiguring burns at the hands of other inmates—and he’s still got a month left to serve (see facing page).

We also discovered that the youngest of the inmate children were being taken out of the jail and isolated on the tiny island of ‘Ata, on the reef just north of ‘Eua iki (see Teenage inmate suffers acid burns.).

Mr Justice A. D. Ford, who took up a position in the Supreme Court of Tonga, last year said, “Initially, it came as quite a shock to me, as a commercial litigator, to realise that in Tonga…and in many other South Pacific countries, there is no special infrastructure in place for dealing with youthful offenders.” He was speaking at the 14th Conference of the Pacific

Judiciary in New Caledonia last year, on the subject of Delinquent Minors and Minors in Danger.

He said in developed countries, like New Zealand, they had in place special youth courts, special legislation, a Commissioner for Children, and social welfare services to focus on creating a “user-friendly” system implemented to suit children and to assure that their problems were dealt with separately to adults.

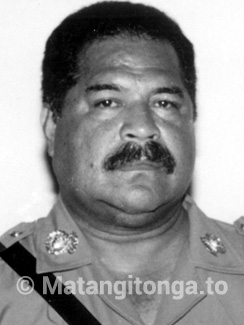

Tonga’s Police Ministry has placed Juvenile Justice on their list of priorities, and Police Commander Sinilau Kolokihakaufisi said they had identified five areas of concern that needed to be addressed. These included the physical discipline of children and the assaulting of children at school and in the homes; sexual abuse; child labour; child pornography and child prostitution; and the administration of Juvenile Justice.

It was imperative, he said, that there be made, “a frame work of laws, policies institutions and practices that determine the manner in which children who have committed or are suspected of committing an offence are dealt with.”

But with no specialised court for children and no separate welfare institution in place, said Sinilau, “this will continue to create problems for the offenders and the Prison’s management.”

Sinilau emphasised that the Police needed to be given powers, “to remove children from streets or homes and places where they usually camp out,” and to return them to their homes or to a place of safety. This also highlighted the need for a child protection system for welfare matters.

He believed that Police should have discretion in determining which cases should proceed and which ones should be diverted from the courts.

He was also concerned about the way in which children were brought to courts, “when a child is referred to the court” he should be “summoned to attend” and not arrested in the adult way, he said.

Sinilau would like to see five basic types of sentences be made available for children in court:

• unsupervised release orders and good behaviour bonds;

• supervised orders and community service;

• restorative justice and group conferencing;

• fines;

• custodial orders and Juvenile detention.

Crime rise

According to Police Prosecutor Lautoa Faletau, youth crime in Tonga is escalating. She said that every week an increasing number of young people passed through court for a range of crimes, including drugs offences, housebreaking, theft, and assault.

Since Lautoa joined the Ministry of Police in 1995, she said she had noticed that the majority of accused appearing before the Magistrate’s Courts were getting younger.

“The age group of most criminals used to be the 20’s to early 30’s…but nowadays they are teenagers and early 20’s. So the majority of criminals now are getting younger. But are we handling it properly?” she asked.

Lautoa said a paramount concern for prosecutors like herself lay in the fact that youth and adult criminals were being kept in the same prisons.

“You put in young boys with sophisticated criminals, what do you expect they will graduate with at the end of their term? With a lot of knowledge on criminal behaviour,” she said.

Lautoa believed that children should be dealt with separately from adults. “If we really want to rehabilitate and reform them, they should be placed in an environment where they won’t be gaining too much criminal knowledge.”

Family support

Mr Justice Ford told the Pacific Judiciary that while Tonga lacked any government funded agencies to deal specifically with young offenders in a crisis situation, there were cultural infrastructures in place that were just as effective. He said one of the early criminal cases he heard in Nuku‘alofa was related to a 12 year old boy who had stolen money from a house.

The boy was the eldest of four illegitimate children who all had different fathers. His mother was in jail. When arrested the boy was eating food he had bought with the stolen money. He spent the night in the police cells and asked the police if he could stay there longer rather than go home and face the mother’s latest de facto.

“He was just a kid and it was impossible not to feel very sorry for him. The situation was clearly all beyond his control.” Mr Justice Ford did not mention what sentence he imposed. He said in this case an uncle of the boy who had heard about his plight stepped in and was looking after him, and it was clear that the boy’s immediate problem had been solved through extended family structure.

“This is something which I have since learned is an extremely important part of Tongan society,” the judge said.

However, Mr Justice Ford went on to report that last year the offence of housebreaking “had taken on epidemic proportions… and the feature we noticed was that in many cases the principal offenders were young Tongans who had come back home from overseas”.

In response the judiciary imposed significant imprisonment sentences on offenders convicted of housebreaking and theft charges. He said that while this measure had decreased the number of crimes in this category, housebreaking continued to be Tonga’s most common criminal offence.

Drugs problem

Meanwhile, the drug problem was on the rise as well, prompting Tonga’s Chief Justice G. Ward to issue a press release in June last year to declare that the sentence for the possession of any drug in small quantities for personal use or others would result in imprisonment.

A success story in improving the system was the birth of the Alcohol and Drug Awareness Centre (ADAC) in 1998—deemed “a holistic assessment, treatment awareness and education service” appearing nowhere else in the South Pacific. Tonga’s ADAC received commendation and positive response from other South Pacific nations like the Marshall Islands, Samoa, Fiji, and further to South East Asia, and the Philippines who all wished to adopt a similar model.

The ADAC administrator Sila Siufanga, believed that a lot of the youth crime stemmed back to dysfunctional families, social ostracism, and a weak system in place to reform and rehabilitate juveniles. He stressed there was an urgent need to establish a juvenile justice system, he said: “Now, now, there is no tomorrow. Now!”

Sila works with problem youth and receives referrals from the courts, which he said had increased from one case in 1998, to 17 last year. His report illustrated that 52 per cent of the ADAC clientele were between 12 and 20 years old.

While the ADAC program is a positive sign of reform, it does have a hefty price tag attached to it, and the program costs $40,000 pa‘anga a year to operate.

Abandoned

Sila said that there was also a need for other services like Legal Aid for those who could not afford a lawyer, and Social Services for abandoned youth. He said that most of the time children just wanted something to eat and somewhere to sleep. “When he’s well fed and has a bed… nothing happens,” he said.

Sila also advocated the need for the creation of juvenile detention centres and a Court to deal with children separately. “Children shouldn’t be locked up in the cells,” he said.

“They need to produce a “user-friendly” environment for the youth where they will have access to sports, educational facilities, vocational type things, out of the cell.”

He stressed that Tonga’s current judicial system created a lot of fear and anxiety, and the reported “violence and abuse” in custody may deter or hinder the truth being told.

Another major concern to Sila was the availability and easy-access of pornographic material to youth. He said that on occasions he conducted follow-ups on clients and asked them where they got their pornographic videos from and they replied, “the video shop.”

He said this was a clear sign that something must be done about it. “Our censorship is so weak that our kids can get their hands on it. “Most of the movies they show here in Tonga are full of violence.”

Interestingly, Tonga has no laws governing censorship, and nothing to reform this is in the pipeline. People who work with juvenile offenders believed that the government should be just as interested about protecting children’s rights, as they are about promoting economic reform and environmental protection.

Deterrents

Under the current system several methods are used to deter youth from committing crimes. One of them is the referral to ADAC, which acts as a “Bridge of care and support in rehabilitating” especially cases dealing with alcohol and drugs.

Others forms of punishment include whipping with a light rod or cane to a maximum of 20 strokes, or to imprisonment to a term equal to that of an adult offender.

Whipping

Mr Justice Ford said he thought whipping would be “a more effective deterrent of punishment than imprisonment.” But he soon discovered that offenders with prior convictions “had been whipped, but it had not stopped them from re-offending.”

It was found that the number of drug-related offences were climbing and “most of the offenders are young and, all too frequently, still at school.”

In a meeting last month in Fiji, one of the issues on the agenda was advocating Restorative Justice as a means of counteracting the problems amongst youth.

Justice Ford agreed that restorative justice had its place in society when he said: “The court has long recognised that apologies and reconciliations are important and valuable features of Tongan custom and genuine contrition demonstrated in the customary Tongan manner.” This involved the presentation of gifts by the offender’s family to the victim or the victim’s family, and was likely to play a significant part in the mitigation of penalty.

“The customary reconciliation process is… the historical Tongan equivalent of the modern New Zealand restorative justice program, in that it places emphasis on the offender accountability and victim restoration.”

There remains, however, an assumption that a country that ratifies the U.N Convention on the Rights of a Child immediately adopts the regulations outlined in the Convention. So in the case of Tonga, although our laws are silent on some matters, the regulations under the convention still apply.