Bill Emmott, a former editor-in-chief of The Economist, is co-director of the Global Commission for Post-Pandemic Policy.

By Bill Emmott

In the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic, it was common to divide countries and their responses according to their political systems, with many attributing China’s success in controlling the virus to its authoritarianism. As of late 2020, however, it is clear that the real dividing line is not political but geographical. Regardless of whether a country is democratic or authoritarian, an island or continental, Confucian or Buddhist, communitarian or individualistic, if it is East Asian, Southeast Asian, or Australasian, it has managed COVID-19 better than any European or North American country.

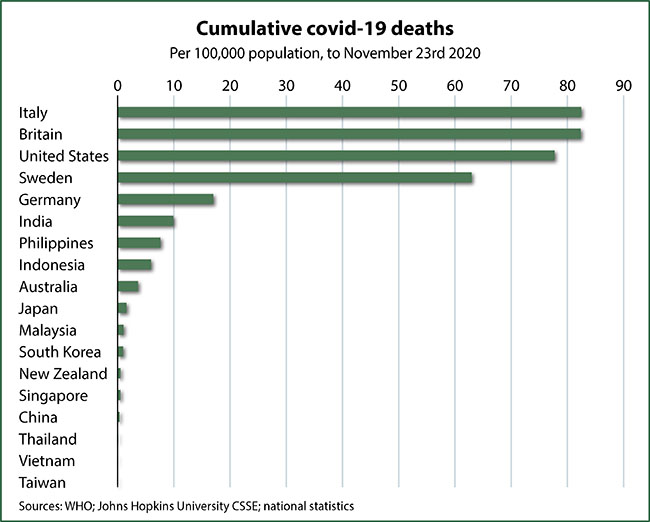

While this line is not exactly hemispheric, it is close enough to be suggestive. Even Asia’s worst performers (in public-health terms) – such as the Philippines and Indonesia – controlled the pandemic more effectively than did Europe’s biggest and wealthiest countries. Notwithstanding reasonable doubts about the quality and accuracy of the reported mortality data in the case of the Philippines (and India), the fact remains that you were much likelier to die of COVID-19 in 2020 if you were European or American than if you were Asian.

Comprehensive, interdisciplinary research is urgently needed to explain these performance differentials. Because much of our current understanding is anecdotal and insufficiently pan-regional, it is vulnerable to political exploitation and distortion. To help all countries prepare for future biological threats, several specific questions need to be explored. First is the extent to which the experience of SARS, MERS, Avian flu, and other disease outbreaks in many Asian countries left a legacy of health-system preparedness and public receptiveness to anti-transmission messaging.

Clearly, some Asian countries have benefited from existing structures designed to prevent outbreaks of tuberculosis, cholera, typhoid, HIV/AIDS, and other infectious diseases. For example, as of 2014, Japan had 48,452 public-health nurses (PHNs), 7,266 of whom were employed in public-health centers where they could be mobilized quickly to assist with COVID-19 contact tracing. Although occupational definitions vary, one can compare these figures with those for England, where just 350-750 PHNs served 11,000 patients in 2014. (England’s population is roughly half the size of Japan’s.)

We also will need a better understanding of the effect of specific policies, such as rapidly closing borders and suspending international travel. Likewise, some countries did a much better job than others at protecting care homes and other facilities for the elderly – especially in countries (notably Japan and South Korea) with a high proportion of people over 65.

Moreover, the effectiveness of public-health communications clearly varied across countries, and it is possible that genetic differences and past programs of anti-tuberculosis vaccination may have helped limit the spread of the coronavirus in some areas. Only with rigorous empirical research will we have the information we need to prepare for future threats.

Many are also wondering what Asia’s relative success this year will mean for public policymaking and geopolitics after the pandemic. If future historians want a precise date for when the “Asian Century” began, they may be tempted to choose 2020, just as the US publisher Henry Luce dated the “American Century” from the onset of World War II.

But this particular comparison suggests that any such judgment may be premature. After all, Luce’s America was an individual superpower. Emerging victorious from the war, it would go on to claim and define its era (in competition with another superpower, the Soviet Union). The Asian Century, by contrast, will feature an entire continent comprising a wide range of countries.

In other words, it is not simply about China. To be sure, the rising new superpower has been notably successful in coping with the pandemic after its initial failures and lack of transparency. But its scope for asserting systemic superiority is circumscribed by the fact that so many other Asian countries have been equally successful without Chinese assistance.

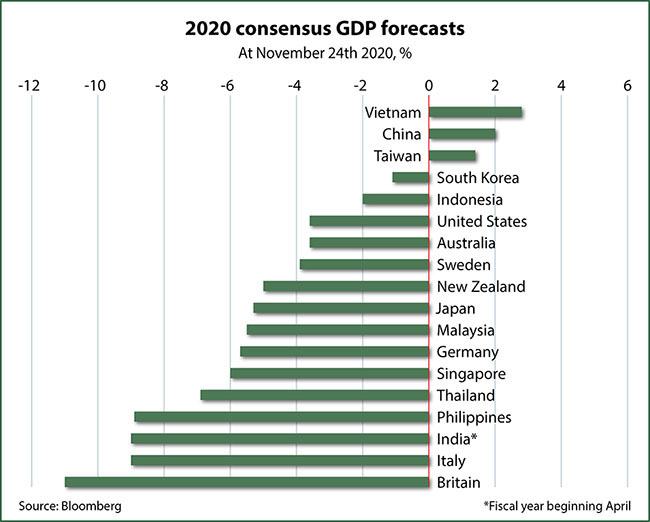

The post-war comparison also may be premature for economic reasons. Asian countries’ economic performance in 2020 did not match the success of their pandemic response. While Vietnam, China, and Taiwan have beaten the rest of the world in terms of GDP growth, the United States has not fared too badly, despite its failure to manage the virus. With forecasts pointing to a 3.6% contraction for the year, the US is in better shape than every European economy, as well as Japan, Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand, the Philippines, and others in Asia. The difference is largely a function of interconnectedness: compared to the US, many Asian economies are more exposed to trade and travel bans, which cut deeply into the tourism industry.

Although China’s public-health and economic outcomes have been better than the West’s in 2020, it has neither found nor really sought a political or diplomatic advantage from the crisis. If anything, China has become more aggressive toward nearby neighbors and countries like Australia. This suggests that Chinese leaders are not even trying to build an Asian network of friends and supporters.

How China approaches the issue of international debt restructurings – especially those connected with its Belt and Road Initiative – will be a key test in 2021. But, of course, the US and the rest of the West also will be tested, and on a wide range of issues, from international finance to sociopolitical stability.

It may be too soon to announce a new historical epoch; but it is not too early to start absorbing the lessons of Asia’s public-health successes.

Copyright: Project Syndicate, 2020. www.project-syndicate.org