by Eleanor Gee and Finau Fonua

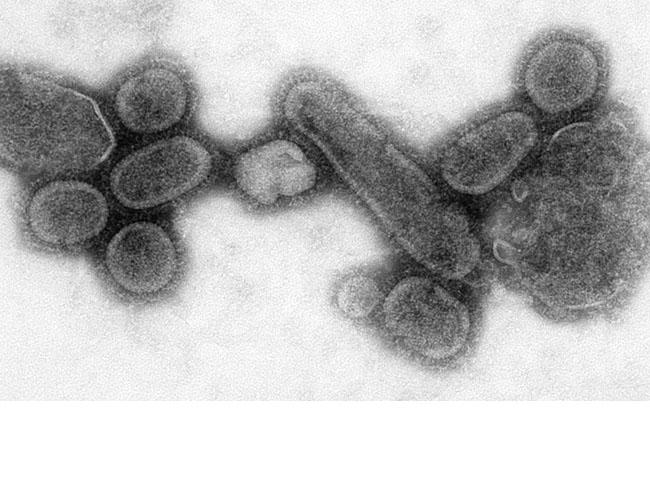

This month 100 years ago, the Kingdom of Tonga was in a state of distress and alarm after a deadly influenza virus reached its shores, infecting most of the population and killing between 1,000 to 2,000 people (an estimated 4 – 8% of the population at the time) between November 1918 and January 1919.

The mahaki faka‘auha - the disease that kills, brought Tonga to a standstill. Government and most businesses were closed, while plantations became overgrown with weeds as there were not enough able men to work. Church bells fell silent as no one was well enough to ring them.

No wireless communications and the lack of newspapers meant no information about the illness and potential treatments reached communities across the islands and although news was spread by word of mouth, the disease spread just as quickly.

Such was the effect of the 1918 influenza pandemic also known as the “Spanish Flu” (because Spain was the first to report it), the worse flu outbreak in recorded history. Globally, the Spanish Flu is estimated to have killed up to 100 million people.

A century later, the memory of the Spanish Flu epidemic lingers in families who lost loved ones in Tonga, where the population had little or no natural resistance to the disease.

“My mother said it was a terrible time”

‘Ilisapesi Tonga Lupeitu’u, 87-years-old from Pahu recalls her mother’s stories when the influenza struck Tongatapu. She said that her mother, ‘Ofa, was expecting at the time.

“When the influenza struck, my mother was pregnant and due at the same time. She had moved [from Nuku’alofa] to be with her mother (my grandmother) at Tatakamotonga and to give birth there.”

“My grandmother died of the influenza. And after my mother gave birth to her second son, Viliami, he also died from influenza. My mother said it was a terrible time and there were a lot of deaths. She could hear the families in the houses nearby crying for their dead relatives.”

She said when her grandmother died, her body had to be taken away in a cart pulled by a family member and he had to dig a grave to bury her in Tatakamotonga.

“My parents survived the influenza, as well as my older brother Siketi.”

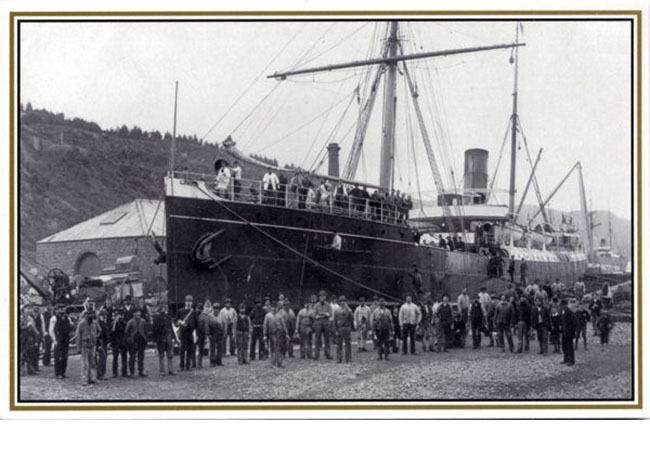

SS Talune

The disease reached Tongatapu on 12 November 1918 with the arrival of the sea vessel SS Talune from Auckland via Samoa, which carried with it 71 sick passengers and crew.

Two days prior to the arrival of the SS Talune in Tonga, Dr N.J. Bailey, the acting Chief Medical Officer for the country and only doctor in Tongatapu, had left for Fiji to restock supplies, leaving Dr Semmens, the only medical physician in Vava’u and Tonga at the time as the last line of defence against the flu.

On reaching Vava’u on 10 November 1918 from Samoa, the SS Talune breezed through without any intervention and was allowed to continue on to Ha’apai

According to a thesis (‘Setting a Barricade against the East Wind: Western Polynesia and the 1918 Influenza Pandemic’) written by academic John Ryan McLane, the first recorded death from Spanish Flu in Tongatapu was a 21-year-old man named Tevita Tualau who passed away from the disease on 15 November – only three days after the SS Talune docked in Nuku’alofa on 12 November.

McLane reported that prior to its arrival to Nuku’alofa, the SS Talune had been stopped in Ha’apai and boarded by two Tongan inspectors, an Acting Port Health Officer and a Customs Officer, both of whom fell ill the next morning and died only a week later.

“People were buried like dogs”

The ruler of Tonga at the time was 18-year-old Queen Salote Tupou III, monarch for less than a year, having assumed the throne from her late father King George Tupou II after he passed away on 5 April 1918. She also had caught the flu but was strong enough to care for her husband, Tungi, and their newborn child.

The virus made no distinctions and the Queen Dowager Takipō (25) died on 26 November 1918 from the flu.

In her later years, Queen Salote was interviewed by the Canadian anthropologist Elizabeth Bott Spillius about her experience of the Spanish Flu epidemic.

Queen Salote told Spillius: “There was no social life—people crept into their houses to die. Some died because they were too weak to get food. People were buried like dogs – no ceremonies, just bundled into the graves. The people were so distressed by having their dead buried in pits together that they were going round digging them back up again.”

At one stage during the epidemic, silence reigned in Nuku’alofa, with the only reported sound the creaking of carts piled with dead bodies led by a relief party, to bury them. On other islands, the group death rates were higher with no one left to bury the dead.

Tales of fortitude

An Australian missionary, Reverend Dr Earnest Collocott, who was living near Nuku’alofa at the time, recorded numerous stories of fortitude that occurred during the influenza. He commended the efforts of an expat nurse Coo Baker – the youngest daughter of Reverend Shirley Baker.

Rev. Collocott recounted: “Coo Baker, who was living in Lifuka with her two sisters, happened to be in Nuku’alofa”. Day by day, and far into the night, she strove, almost past human strength, to win the sick back to life…As she walked along the dark and empty roads swarms of hungry dogs, whom no one was able to care for, crowded after her.”

“A young German, Carl Riechelmann, sick himself, rode daily to the help of others, till he fell from his bicycle and was taken home to die”

“In a Tongan home, relief visitors found a tiny mite of a girl, who seemed no more than four or five years of age, nursing grandparents, parents, brothers, and sisters”

“A Tongan man, ill and haggard, came to the mission house for medicine. Rodger Page told him he should be at home in bed, and the man, crying, “But it’s for my child,” fell unconscious on the verandah….”

Criticism of leadership

According to the British perspectives, no leadership was provided by government, the Royal Family or the nobles during the crisis. The British Consul in Tonga at the time, Islay McOwan, organized a relief party and supplies from Australia to alleviate Tonga’s dire situation.

McOwan was heavily critical of Tonga’s independent Government. In a scathing letter to the British Governor of Fiji, Cecil Rodwell, McOwan accused Tonga’s nobility of apathy and singled out Hon. Tevita Tuʻivakano, Tonga’s Premier at the time.

“The most discouraging feature of the outbreak was the apathy and indifference of the native chiefs to the suffering and distress of their people and I regret to say that the Premier was no exception. On the day that the relief work was started he was out driving in his motor car apparently quite recovered. I appealed to his assistance in obtaining labour for the work of burying the dead but the same afternoon he sent a message to me that he was unable to obtain any men. From that time until conditions had considerably improved I neither saw nor heard of him again…”

The very young Queen Sālote was also considered to lack leadership skills at the time according to author Elizabeth Wood-Ellem, who stated in her book Queen Salote of Tonga: The Story of an Era, 1900-65, “the Queen failed this first serious test of her leadership. Her government broke down and took no action whatsoever to ameliorate the effects of the epidemic, either locally or nationally.”

Samoa and the SS Talune

Perhaps the country worst hit by Spanish Flu was Samoa – then a colony of New Zealand. It is estimated that at least 90% of Samoa’s population became sick with the Spanish flu and over 8,500 people perished (nearly a quarter of Samoa’s population at the time). In contrast, American Samoa suffered no fatalities after its administration implemented strict quarantines – turning away any vessels with sick passengers.

In 2002, New Zealand Prime Minister Helen Clark – who was attending Samoan independence celebrations in Apia – offered a national apology to Samoa.

Clark stated “In particular we acknowledge with regret the decision taken by the New Zealand authorities in 1918 to allow the ship Talune, carrying passengers with influenza, to dock in Apia.”

For many families in Tonga, lives were changed forever as children were orphaned and family members lost - the impact of the influenza epidemic was felt over the following generation.

--

How did the Spanish Flu affect your family? If your family has ancestral memories of the 1918-19 Spanish Flu epidemic in Tonga, please feel free to contribute your stories in the comments section below this article.