By the East Asia Forum Editorial Board, Crawford School of Public Policy, College of Asia and the Pacific, The Australian National University.

The United States abandoned economic leadership in Asia four years ago. Rather than promote and strengthen the multilateral institutions and frameworks that underpin Asia’s prosperity, the United States under President Trump began systematically undermining them: from the WTO, WHO and Paris Agreement, to military alliances with Japan and South Korea, bilateral trade ties and cooperation in regional forums.

The message that Asian policymakers received was crystal clear: Asia is too reliant on an increasingly unreliable America. The damage from the Trump presidency is likely, sadly, to be permanent.

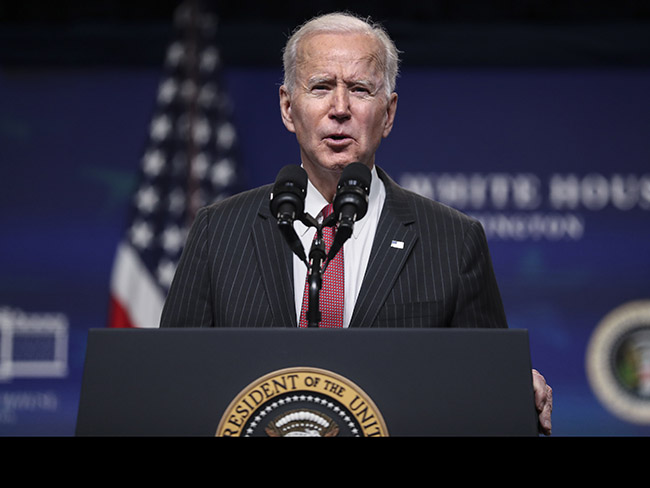

While President Biden is a refreshing change, three things still weigh on the minds of Asian policymakers.

First, Asian policymakers recognise that Trump was not an accident. He was the product of long-standing deep structural challenges in the US economy and society. Addressing those challenges will be a difficult, long-term proposition. The Democrats winning the White House, House of Representatives and Senate means Biden has more room to manoeuvre in addressing those challenges. But failing to secure a majority big enough to defeat the filibuster means cooperation with the Republicans — a party suffering a deep identity crisis — is still essential.

Second, Biden is swamped with domestic problems. American presidents in the past have had to deal with race riots, pandemics, recessions, political polarisation and the alleged criminal acts of their predecessors before, but never has a president had to deal with all of them at once. With so many problems at home, Asian policymakers fear Biden will be too preoccupied and have too little political capital to spend on foreign policy issues in the region.

Finally, although Biden has begun reframing US foreign policy, there are still plenty of signals from Washington that worry Asian policymakers: from aggressive ‘Buy American’ rhetoric to a continuation of a hyper-securitised approach to China that under-weights the economic role China plays in the region and the role that economic prosperity plays in Asia’s national security.

Counterweights

Biden has his work cut out winning over a sceptical Asia. The reality is that both need each other: Asia needs the counterweight of America, and Biden needs Asia if he is to deliver on his foreign policy objectives. What can Biden do to instil confidence in a region still battered and bruised from four years of the Trump administration waywardness?

In the East Asia Forum lead article this week, Adam Triggs suggests one answer: using Indonesia’s upcoming G20 host year in 2022 to strengthen the multilateral institutions that Asia relies upon and which underpin long-term US influence in the region. In turning its back on multilateral institutions, the United States surrendered one of the most powerful weapons in the US arsenal: the ability to shape global rules and institutions. The problem is that too many multilateral institutions are in desperate need of reform. As these institutions atrophy over time, so does US influence as a patchwork of competing institutions emerge.

There are several major global institutions that need reform, Triggs suggests. The global trade rules need updating while the IMF and World Bank’s outdated governance structures weaken their legitimacy, funding and effectiveness. The World Health Organization’s budget is smaller than that of most big hospitals and too much of its funding is earmarked, while the International Energy Agency’s membership still excludes a majority of the world’s energy consumers.

‘The consequences of these out-of-date institutions are the same: more fragmentation and less US influence’, says Triggs. ‘As the funding, legitimacy and effectiveness of these institutions dwindles, regional competitors emerge’. For the WTO, it’s a plethora of plurilateral and bilateral trade agreements. For the IMF, it’s the European Stability Mechanism, the Chiang Mai Initiative and hundreds of bilateral currency swap lines. For the World Bank, it’s the Asian Development Bank, the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and many others.

For the first time in more than 10 years, President Biden has a window of opportunity to fix this. With the White House and both houses of Congress in alignment, the United States can lead reform in these institutions and create new rules where they are lacking today.

‘Historically, successful reforms in global governance have required at least three things’, says Triggs: ‘leadership from the President of the United States, approval from the US Congress (at least when funding is required) and a quorum of major countries that support the change. For the first time in more than a decade, all three pieces of the puzzle could be in place’.

An overwhelming quorum of countries support the reform of global institutions, especially in Asia. ‘Indonesia will host the G20 next year and has been a vocal leader on the case for WTO reform’, says Triggs. ‘Asia’s bitter memories of the IMF’s past failings have seen it spend decades calling for reform. A region desperate for investment will benefit substantially from reformed and better coordinated development banks while climate change is an opportunity for constructive engagement on a common priority between the United States, China and the Asian region’.

The pressure on President Biden is intense. The challenges he faces are substantial, and correlated. Expectations are high, both at home and abroad, and the stakes are high if he fails. In foreign policy, his best bet is to target something substantial that will win over a hopeful but still sceptical Asia, that will cement a productive US role in the region and that will endure long after his presidency. Reform of global institutions should be top of his list.

The East Asia Forum Editorial Board is located in the Crawford School of Public Policy, College of Asia and the Pacific, The Australian National University.

https://www.eastasiaforum.org/2021/02/22/how-can-biden-win-over-a-still-...